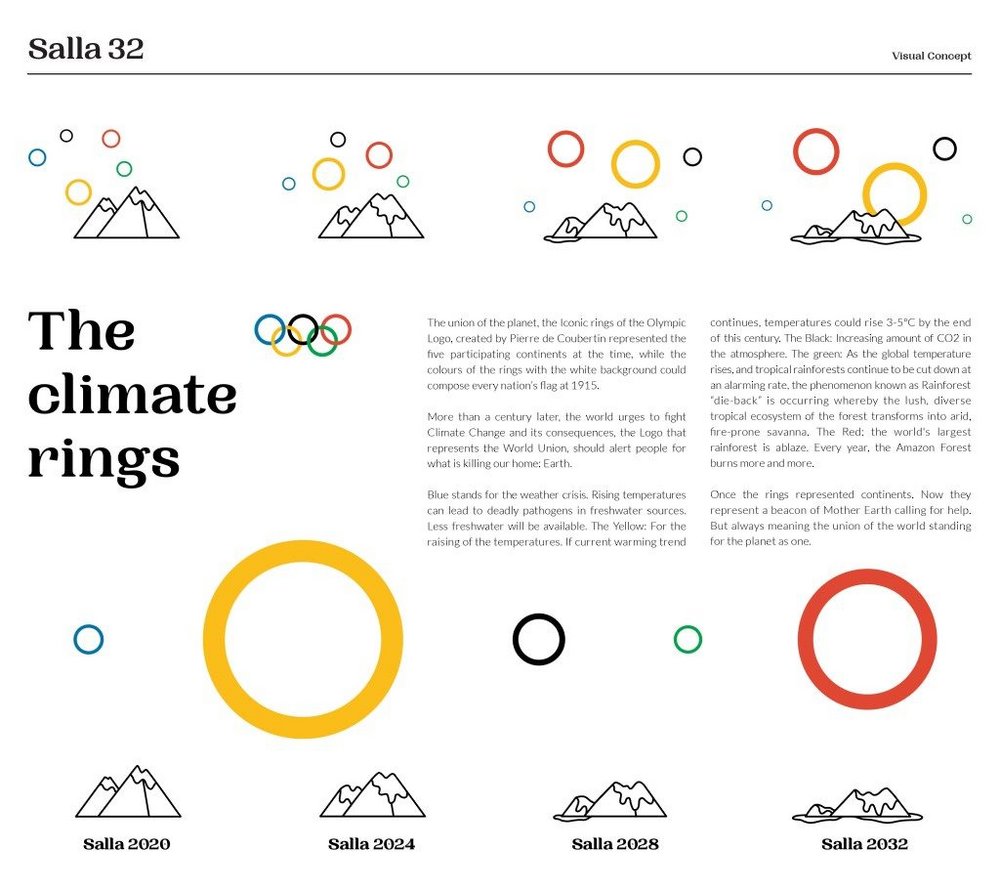

Contagious recently covered a hoax bid from the snowy town of Salla, Finland to host the 2032 Summer Olympic Games. The Salla 2032 campaign was a joint effort from official tourist board House of Lapland and Brazilian agency Africa, São Paulo and was designed to resemble a legitimate proposal from the coldest place in Finland to host the summer games.

Following public outrage and confusion, the campaign was revealed as a carefully disguised initiative to raise awareness about the effects of global warming. The campaign name was changed from Salla 2032 to Save Salla across all touchpoints, with a new message about the need to act on climate change so that Salla never has an opportunity to host the Summer Olympic Games.

The campaign website also featured information on how individuals and businesses in different sectors can do their bit to prevent global warming, developed in partnership with Drawdown, a leading resource for climate solutions.

To find out more about how this idea mobilised the town of Salla, we spoke with House of Lapland marketing manager Veli-Pekka Ojama. From the agency, we heard from creative director Nicholas Bergantin and director of special projects Juliana Leite. They told us that:

- The eco-tourism aspect of Save Salla took a backseat to the main objective of raising awareness about climate change

- The concept was conceived by the agency and pitched across the globe to find a partner city

- During the first stage of the campaign, the town kept the reveal a secret until the launch press conference

- The key KPIs of the campaign were around press coverage and share of conversation. The campaign was covered by 118 countries and resulted in 7.5 billion media impressions

What exactly is the House of Lapland?

Veli-Pekka Ojama: House of Lapland is a publicly owned destination marketing company and we’re the official marketing and communication office for Lapland. We’ve been running for seven years now and our mission is to make sure that Lapland is an attractive destination for travellers, filmmakers, businesses and talent seeking nature, outdoor and cultural experiences.

What are its key challenges?

Ojama: Our main challenge is the climate crisis and that’s the area that we want to focus on. Fortunately, ecological values and natural sustainability are a huge trend now, which provides a lot of opportunities for us in our marketing and how we talk about our locations.

Who are its competitors?

Ojama: We like to look at our competition set as widely as possible. Of course we have close competitors across other Northern Scandinavian countries, but we compete against every nature and outdoor-related destination across the whole world. Coming out of Covid-19, some people will be looking for destinations away from crowded big cities out in the silent, open countryside and we’re competing against those types of destinations too.

We have a special projects department at Africa which is an incubator for crazy ideas. That’s where Save Salla started, not with a brief but with an agency ambition to help the global climate emergency.

Juliana Leite, Africa, Sao Paulo

How did the Save Salla concept originate?

Juliana Leite: We have a special projects department at Africa which is an incubator for crazy ideas that we attempt to make happen. In September 2019 an idea was pitched internally that asked whether we could get one of the coldest places on earth to host the Summer Olympic Games to raise awareness about climate change. Our CCO loved it and that’s where Save Salla started, not with a brief but with an agency ambition to help the global climate emergency.

Nicholas Bergantin: As the 2024 and 2028 games had already been awarded to Paris and Los Angeles, we targeted the next undecided Olympics in the calendar, which was the 2032 games. Also, this decade (between 2030 and 2040) will be the turning point in the crisis according to scientists, so 2032 made all the more sense.

How did you decide which city would be chosen to submit the bid and why was Salla the winning choice?

Bergantin: As we started to look into what scientists and experts were saying about the problem we realised that the closer you are to the poles, the greater the effects are. That’s where the emergency is happening right now. We then set out as a team to find a cold place that had the same beliefs and commitment to the climate emergency as we had. We had talks with a lot of cities across Russia, Iceland, Canada, Greenland and there was even one city – that I won’t name – which basically told us that the planet increasing by a few degrees would actually be beneficial for new opportunities. By December 2019 we still hadn’t found a place that aligned with what we were looking for, but then we found Salla and House of Lapland. The chemistry we had was undeniable and Lapland told us that they needed this campaign right now because of how much they were suffering due to global warming. We had a lot of conference calls with the local councils, the board of House of Lapland, the city’s mayor and following those talks we knew this was the right place for the campaign.

How did House of Lapland ensure that it followed all the entry requirements to qualify for a real bid? Was this important to the execution?

Bergantin: Once we started to craft the touchpoints of the campaign we researched all the different requirements that a city must accomplish to qualify for a legitimate bid. We spoke to Finnish scientists who told us that if the temperature keeps increasing it will lead to pests like mosquitos coming into the region and spreading tropical diseases that will infect the reindeer of the country. [This resulted in the mascot] Kesa: the overheating reindeer with a mosquito on its nose. For the logo, we chose a melting image of the Sallatunturi mountain, which is a beautiful, magnificent piece of nature whose peaks are already melting due to climate change.

We created a ‘coming soon’ Salla 2032 store on our website that sold merchandise like towels and flip flops for people to dress appropriately for the hot weather. We also discovered that we needed a specific bid book, so we crafted a 220-page intention book that contained locations for various events. For example, a frozen lake could now be used as a location for the aquatic marathon, or ski mountains could be repurposed as mountain biking locations. This book was then hand-delivered by the city’s mayor to the International Olympic Committee’s headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland. We did everything a real candidate city must do in order for everyone to believe that this was a real bid.

We needed everybody in the city of Salla to come together around the idea. We mobilised an entire 3,400 person city which was just like an actual bid for the Summer Olympic Games.

Nicholas Bergantin, Africa, Sao Paulo

What was the launch strategy and how did the campaign then transition into Save Salla?

Bergantin: The initial launch was planned for March 2020 but then the pandemic stopped everything and we had to wait for the right window of time to launch. Then, towards the end of the year as the US election was ramping up, Joe Biden had on his agenda to return to the Paris Climate Accord agreement if he won. Which he did, hours after his inauguration in January. We decided to drop it a week [after] while climate change was already in the public consciousness.

Leite: We launched in two phases, the first attempting to convince the world this was a real bid and ensuring the people of Salla kept the secret.

Bergantin: This was so much more than just a client-agency relationship because we needed everybody in the city of Salla to come together around the idea. We mobilised an entire 3,400 person city, which was just like an actual bid for the Summer Olympic Games. After the bid book was delivered, the world started questioning ‘What the hell is going on?’ and sharing tweets that said: ‘No, please don’t let the games in Salla happen.’ As the wave of those conversations came in, even the Olympic Committee of Finland – which didn’t know about the idea beforehand – publicly issued a statement saying they didn’t support Salla 2032.

We had a lot of anxiety during this waiting period and even briefed the mayor of Salla about what he should do when the phone started ringing, emails flooded in and requests for interviews were mounting. We had to wait so we could build critical mass of conversations online before the pivot. Once we’d reached that, we organised a press conference with Salla’s mayor and that’s where we revealed that this wasn’t a celebration, but a condemnation of what was happening to the region due to climate change. At that moment the website changed from Salla 2032 to Save Salla and the true ambition of the campaign was revealed.

Once the first domino toppled there was no way of controlling it, with Salla becoming the most mentioned city on Twitter for three weeks running [and] more than fifty Finnish embassies across the globe tweeting about the campaign.

Nicholas Bergantin, Africa, Sao Paulo

What did the media plan look like for this campaign? Did you require separate strategies for the two phases?

Bergantin: We prepared two press releases for the campaign. A media kit with all the campaign assets was sent to journalists and influencers requesting them to back Salla as the host of the 2032 games.

Leite: Importantly, this initial press release directed people who wanted to find out more about Salla 2032 to our press conference which would explain everything people wanted to know about the city’s bid.

Bergantin: While this press conference was happening, all the campaign assets, marketing across social media and the website content changed from Salla 2032 to Save Salla – with a new press release sent out that contained everything about our fight against global warming. There was zero paid media behind the campaign, everything was organic.

What were the results of the campaign?

Bergantin: We had more than fifty Finnish embassies across the globe tweeting about the campaign, which truly helped with the global reach. Then Greta Thunberg was also a fantastic asset for us and after she tweeted ‘Save Salla’ we saw everything skyrocket. Once the first domino toppled there was no way of controlling it, with Salla becoming the most mentioned city on Twitter for three weeks running. We had coverage in 118 countries from the likes of the Gazzetta dello Sport in Italy, The Washington Post in the US and the Guardian in the UK.

Ojama: There was even an article in the Helsinki Times about how Save Salla had helped put Finland on the map in a positive way. In total we generated $157m in earned media and 7.5 billion media impressions, but most importantly conversations around global warming on social media increased by 879%.

What did the partnerships with Fridays For Future and the Project Drawdown bring to the campaign?

Bergantin: We couldn’t just tell people this was a problem, we also had to give people information about what they could do to help the situation. With Fridays For Future and Project Drawdown, we crafted a very detailed list of things that people and business of all sizes could do or implement to help make a positive impact on the environment and support saving Salla.

As a small destination with a limited budget we really have to focus on doing something different with our work to get awareness. With Save Salla, we created something designed to get our voice heard above the noise.

Veli-Pekka Ojama, House of Lapland

With an agency in São Paulo, Brazil and a client in Lapland, Finland, how smooth was the working relationship?

Ojama: As climate change is a global threat, it was nice that this campaign took international collaboration to happen. It really went well. Of course, we had to adjust our thinking and way of working because of the pandemic and the different time zones, but we adapted through Microsoft Teams calls and WhatsApp messaging.

How is Save Salla a continuation of House of Lapland’s overarching strategy?

Ojama: As a small destination with a limited budget we really have to focus on doing something different with our work to get awareness and eyeballs on us. In the past we created a Spotify album of soundscapes where nature was the artist, with the content made of ambient sounds of Lapland to transport anybody here no matter where they were in the world. Just as with Save Salla, we created something designed to get our voice heard above the noise.

Bergantin: One of the main problems that brands face nowadays is relevance and getting people to pay attention to their advertising. Consumers experience an influx of new information every day and people generally ignore or don’t care about what you have to say. But with Save Salla people actually cared and paid attention to the campaign, establishing Lapland as one of the most sustainable places around the world. Also on social, people from places like India or Argentina were saying how they’d never considered Finland as a travel destination before and were considering travelling to Salla as it seemed like a great place to visit.

What has been your single greatest learning from this campaign?

Bergantin: For me it’s that walls to creativity are not real; they are just barriers you build up around your mind or geographical frontiers on a map. Your initial reaction to this campaign idea may be ‘You can’t do this, Finland is on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean,’ but if you have something that you want to share, why not find someone in Finland, South Africa or Antarctica to work with you?