Photo by Renato Trentin on Unsplash

Professor Jenni Romaniuk is the associate director at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science.

Ehrenberg-Bass is without question the most influential marketing research institute on the planet and Romaniuk has carved out a reputation as the world’s foremost expert on distinctive assets, publishing a book on the subject in 2018.

We spoke with Romaniuk about what distinctiveness means in the context of brand building, why it’s vital, and how best to measure it.

What does distinctiveness mean in the context of brand building?

Distinctiveness is looking like you and not like others so other people can easily identify that something is from your brand. We talk about distinctive assets because we break it down into specific elements like colours, logos and names. It’s a specific visual or audio or sensory cue that just tells people who any piece of collateral is from.

So why is it important for brands to be distinctive?

There is so much marketing going on from different brands and every brand has competitors. By being distinctive it’s easier for someone to know something is from your brand, and it means that whenever they encounter something that you’ve put out, it attaches to your brand in their brain.

And the easier that process is, the more likely it is when you try to build anything else, for example an association or an emotion, people will know where to put it in their brain.

Is there any research that quantifies the advantage of having a distinctive brand?

It’s hard to say because branding is a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. You have to have the brand, but sometimes it’s not the only thing that you need in order to get bought. If you have the greatest brand but the weakest distribution, it’s not going to convert to sales.

So we talk about systems and laws of growth, of which branding and distinctiveness are a really important part, so people know it’s your brand and they don’t have to expend a lot of cognitive energy, because we know that if you don’t make it easy, people won’t do the extra work to get to the answer you want them to. They’ll just do nothing.

So it’s not easy to say, ‘if you’re 10% more distinctive you will get 3% more in sales’, because the line between those two things is complicated.

And one of the big challenges is having the metrics to assess distinctiveness. That’s why I wrote my book on building distinctive assets. We kept telling people you need to do good branding and they’d go ‘yep’ and we’d go ‘that doesn't seem very good’, and we realised that there were no metrics to judge how distinctive they are. And so if you can’t measure something you can’t quantify it.

Jenni Romaniuk

What are some of the metrics that are most useful for measuring distinctiveness?

We break down triggers of the brand into different assets. So each particular asset, whether it’s colour, colour combination, a spokesman or a logo, can be quantified in its strength based on fame (which is the proportion of category buyers who when exposed to that without the brand name, it triggers the brand name unprompted for them) or it’s uniqueness (which is how much you own it. Are you the only brand linked to it or do you share it with other brands? The more you share it with others the weaker it is).

Is your experience that marketers are usually quite bad at judging the distinctiveness of their own brand?

Marketers tend to inflate their asset strength, and that’s for a couple of reasons. One is they tend to have the full information about what their brand did, and they don’t understand that the consumer rarely does. Most of the time, the consumer doesn’t see what the marketer saw. So marketers overestimate the effect [of their advertising]. And they underestimate what competitors are doing, because they don’t have full visibility of competitor activity, so they don’t understand where there’s an overlap and a consumer might confuse something they’re doing with the work of a competitor.

The other thing is that marketers tend to notice assets that they’re working on, which usually involves some form of change, and change is the thing that actually weakens distinctive assets.

Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Unsplash

Is consistency paramount when talking about distinctiveness?

People often confuse consistency of form and consistency of use. Consistency of form is that it looks like what it is. So if you are a Coca-Cola bottle you have that shape that is a silhouette and you look like the Coke bottle. Consistency of use would be, for instance, always showing the Coca-Cola bottle in the top right corner of every ad.

Consistency of form is particularly important when you’re building assets, when you’re trying to strengthen an asset and get it to a point where it’s so well known that it basically replaces the brand name. If you play around with an asset too much while you’re building it, you aren’t strengthening the same asset, you’re creating different ones.

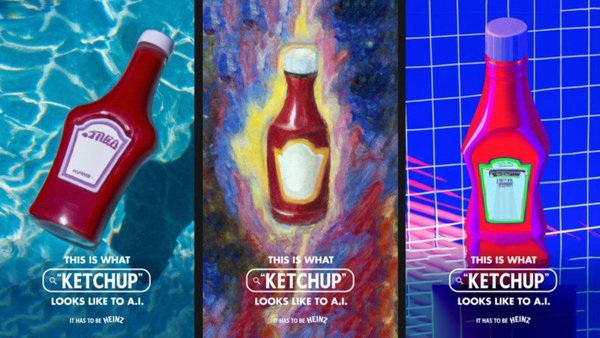

But once you’ve got a strong asset you don’t need consistency of use. Once you have the form in people’s minds, you can start to challenge it and have fun with it.

Take what KFC did with the Colonel. We can understand what it’s doing when it has different actors play the Colonel because we have a consistent form of what the character is. He has the suit, a certain type of tie, the white-hair, the goatee; all of those things are the consistency of form, but now they can play around with the use of [the form] by having women playing the Colonel or people of different ethnicities.

I’ve had discussions with marketers who have tried to impose consistency of use, and that’s when you get the creative constraints that people tend to want to fight against.

How does ‘meaningless distinctiveness’, as espoused in How Brands Grow, fit into all this?

I call it ‘meaning-free’ rather than ‘meaningless’ distinctiveness. A meaning-free asset is one where the strongest meaning is actually the brand. It's not that you pick something totally new, but you actually pick something that has no hurdles to overcome to attach it to the brand name. If you have something that already has a strong meaning to it, that means the brand is constantly fighting against that old meaning that will come to mind when the asset is there.

Do marketers generally understand the importance of being distinctive?

It’s hard to judge, but more and more organisations are putting numbers behind it. And I think when you put numbers behind something, it helps. If you can’t show them an asset is strong, it’s easy for someone to come in and make a case to change it. If you’ve got numbers behind it [...] you know what you’re losing.

Some of my best projects with companies are the ones where after the research nothing happened, because we demonstrated that it was going to either be a bad move or of no benefit.

Photo by Henry & Co. on Unsplash

Do you find that when brands do change they tend to converge around the same trends and themes that have been proven to work, creating more sameness?

Creatives source from their environment and a lot of them are drawing from the same environment [...] I don’t think it’s intentional, it’s just a function of timing.

The one thing I’m trying to push is that you don’t want your distinctive assets to be fashion items.

Think about your wardrobe. You have those items with the trendy colour or the trendy cut – the thing that lets people know you’re in touch with fashion. Then you have those go-to staples you know you look good in and you can wear any place. A distinctive asset needs to be that classic black suit or that little black dress that you know you can pull out for any occasion and you know looks good.

And the more you change it the more you turn it into a fashion item, the more it’s likely to be a product of its time.

Contagious interviewed Jenni Romaniuk as part of a project in partnership with (and commissioned by) Twitter. You can read the resulting article here.