‘ATT has been an almost extinction event within the digital economy’ /

Venture capitalist and prolific marketing blogger Eric Seufert shares his insights into online advertising, ATT, Cambridge Analytica and more

James Swift

/

Photo by Rami Al-zayat on Unsplash

If you want to understand the online advertising ecosystem then you should pay attention to Eric Seufert.

Seufert is a former analyst and marketer who took an interest in freemium business models just as they began to take hold within the digital economy. After jobs at mobile gaming companies – including Rovio, which made Angry Birds – Seufert built a mobile marketing analytics platform, Agamemnon, which he sold in 2017, and now he invests in mobile advertising and gaming startups through his fund, Heracles Capital.

And all the while (or at least since 2012), Seufert has been publishing his thoughts on mobile and online advertising on his blog.

The articles on Mobile Dev Memo are not always easy to read – Seufert lives deep in the weeds of his subject matter and does not seem to have much interest in dumbing down his analysis for lay readers – but they’re worth the effort.

Seufert is arguably the most incisive and prescient commentator on the mobile advertising ecosystem writing today. His analysis of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) framework and its knock-on effects has been leagues ahead of almost everyone else’s coverage, and Seufert is frequently called upon by publications like the Financial Times, New York Times and Wall Street Journal to explain the commercial machinations of the big tech platforms.

We spoke to Seufert to get an overview of what has happened to online advertising in the wake of ATT and what he thinks will happen in the future. What follows is an edited account of that conversation.

A lot of people who write about online advertising tend to have a clear point of view, either as cheerleaders for the industry or doom-mongers. You always seem to come across as fairly disinterested. What’s your overall view of the online advertising industry and targeted advertising specifically? How big are its problems and how troublesome are its externalities, relative to the value it creates?

I think [digital advertising] gets used as a catch-all for a lot of behaviours and a lot of economic outcomes that aren’t really what I would consider to be digital advertising.

In many cases, the entire issue of misinformation gets conflated with digital advertising. Those are two very distinct intellectual spaces, and they don’t really intersect that much.

What caused those two spaces to be seen as overlapping was Cambridge Analytica. I think that’s really unfortunate. To my mind – and I know that this maybe is a controversial opinion – Cambridge Analytica was a distraction. There was no material problem that Cambridge Analytica highlighted except for the fact that it was possible at one point to pull a bunch of user data out of the Facebook API when those users had not consented to that. But everything that Cambridge Analytica did relating to digital advertising was basically snake oil. The problem with Cambridge Analytica was it allowed those two things to be seen as part of the same problem. The reality is Cambridge Analytica was more or less a totally ineffectual marketing agency, a small marketing agency that is portrayed as being much more insidious and consequential, just through its association with [former executive chairman of Breitbart News and Donald Trump’s chief strategist] Steve Bannon. The reality is Cambridge Analytica worked for Trump pro bono. The UK [Information Commissioner’s Office] said after a lengthy investigation that it had no impact on the outcome of the Brexit vote.

There’s no reason to believe that Cambridge Analytica was anything more than a boutique marketing agency that wasn’t really that good at what they purported to do. But it got focused on as being a scandal related to digital advertising and misinformation and abuse of data. And to be fair, they should not have been able to access the data. [But] that data was used to build these psychographic profiles, which if you talk to any performance marketer, or anybody that works in ecommerce, they’ll say, ‘I would never trust that kind of targeting data, I’d rather use previous conversion histories.’

I think that was the flashpoint that allowed these two issues to become conflated. Now, if I think about digital advertising and targeted digital advertising specifically, there are many aspects of it that are absolutely problematic. There are many aspects of it that are invasive of user privacy, that have negative externalities, and I’ve written about this. I wrote an article that was titled, The IDFA [a code that identifies an individual’s device to advertisers] Is The Hydrocarbon Of The Mobile Advertising Ecosystem. I said, just like the hydrocarbon that we extract from the ground, it needs to be at some point excised from the economy because it has these externalities that are not being paid for.

The externalities with real hydrocarbons are pollution, and the externalities of device identifiers and things like cookies are mistrust and adverse effects on people's mental health. These things are not paid for by these firms that benefit from them, and they’re problematic. We don’t know what the size of the internet economy would be if people were more trusting of these systems, if they didn’t feel like they were spying on them or invading their privacy.

Now, whether or not [spying, etc] actually happens with the magnitude that people believe, I don’t know. But that’s a problem in and of itself. People should understand how their data is being used.

What I am willing to say, which I think a lot of people are not willing to say, is there is a trade off. There are benefits to this, too, and those need to be recognised. You might say the detriments outweigh the benefits, and that’s fine. But what I think is disingenuous is when people present this as being totally one sided, that all the apparatus that surrounds digital advertising is completely detrimental to the user. I think that’s an absolutely disingenuous position to take.

Eric Seufert, Heracles Capital

And the main benefit is more relevant advertising for consumers?

Sure, that might be the most obvious benefit from the user’s perspective, but it’s also the fact that these companies [that sell niche products online] can exist in the first place.

There’s a couple of giveaways when you’re speaking to somebody about this that their position is ideological and not fact based. The first is they’ll say, ‘There’s no benefits to any of this and all ad tech is snake oil.’ That’s just demonstrably not true. There’s a lot of academic research to support the value of this technology.

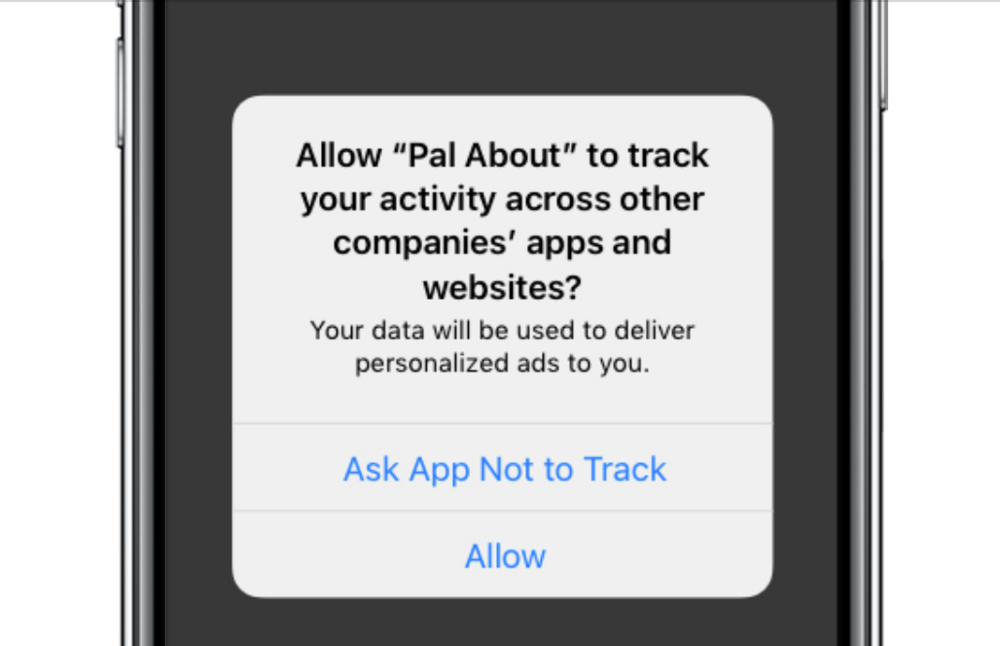

The other red flag is when people say there is value in this ad tech but people can’t possibly understand how their data is used, so they can’t possibly consent. I’m sympathetic to that argument, but I have a much more charitable view of people’s ability to interpret the way that their data is used. And I think that would be supported by the fact that Apple has a consent mechanism for its own advertising system. Apple’s own ads system is not moderated by ATT, but they have an opt-in screen that unlocks the use of their own personalisation system. Now, if Apple is the vanguard of internet privacy, and they say that they believe their users can interpret what they’re saying in this opt-in screen, I would believe them about that.

The New York Times recently published an article to the effect that online advertising was getting worse and people were being bombarded with irrelevant ads from low-rent brands. Do you agree, and if so do you know why it’s happening?

I can’t say that I’ve noticed a meaningful change in the relevancy of ads. I just personally can’t say that. I’m also generally suspicious of articles like that because how could you quantify that?

So first of all, I’d say I'm pretty circumspect of the premise. But if that’s true, then it’s probably as a result of ATT. Because that’s what ATT does, it says, ‘Okay, we're going to disrupt the ability for these platforms to target ads to you based on your behavioural history.’ Therefore the ad targeting is going to get much more oblique and much less personally relevant.

Now, you might say, ‘Who cares? I can live with that.’ But that’s not the only impact. That’s the first-order impact. The second-order impact is that that company can’t acquire as many people anymore. And so the company goes bankrupt, or they can’t afford to run a free product anymore, so they have to start charging a paywall for access, as you’re seeing now with Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook – they have to start adding a VIP tier to the product to claw back some of that revenue that’s lost from the advertising.

Now, again, you might say, ‘I don't care, that’s fine.’ But that’s not a decision that I think most people understood that they were making when they opted out of cross-site targeting with ATT.

You wrote that by introducing ATT Apple had ‘robbed the mob’s bank’, meaning that it was trying to hobble Facebook rather than protect users’ privacy. Do you think that Apple’s behaviour since has borne out your thesis?

Yes because that wasn’t prognostication, that was just a colourful way to describe what I was observing and which was supported quantitatively by the estimates of Apple’s ad revenue growth since ATT. If you look at the estimates that I cited in that article, the ad revenue had grown to be 4X what it was prior to ATT in less than a year, and we’re starting from a multi-billion dollar baseline.

That was in retrospect a provocative headline. And I struggled with that because I want my writing to be taken seriously, and I’m not a provocateur. But at the same time, that provocative headline allowed the article to reach a lot more people. And I think it awoke a lot of people to the machinations of that privacy policy. I think that the prevailing sentiment around that was, ‘Hey, this is just another thing that Apple is doing to benefit the consumer, aren’t they such a great company? And isn’t it so noble that they’re taking on Facebook?’ And what I wanted to draw attention to is the fact that they’re benefiting from this.

Not only are they benefiting from this, they are still utilising behavioural data in the way that Facebook was. [Apple] are still utilising data that is generated by a product that they didn’t create. If someone opens up an app and they make a purchase, Apple knows about that purchase. Why? Because they force you to use their own transaction system to make money on the iPhone or on iOS, because then they can take a cut. And so they say, ‘Well, since we process the transaction… then that’s our first-party data’.

From a consumer standpoint, I don’t think there's any obvious difference between what Facebook is doing and what Apple is doing for ads targeting.

What has been the effect of ATT on brands and advertisers?

I don’t want to seem like I’m overstating this, but it’s been devastating. This has been an almost extinction event within the digital economy.

Again you might say, ‘That’s collateral damage, but this needed to be done’. But even if you accept that it was better for privacy, I think you have to weigh that against the economic consequences. Go talk to any ecommerce advertiser and they’ll tell you this has been disastrous for their business. Go talk to any mobile game developer, they’ll tell you the same thing.

Eric Seufert, Heracles Capital

I worked at this company, Wooga, that was acquired by a bigger company, Playtika. They had earnings two days ago [28 February]. They said, ‘We can’t make any new games, they’re impossible to get users for. So we’re just going to focus all of our efforts on existing titles.’ That’s a public, multibillion dollar company. If anyone had the resources to build the technologies and the tools to adapt to [ATT], it’s them, and they’re saying they can’t.

And what has ATT meant for the platforms that sold targeted advertising as part of their business model?

I wrote a really long piece a couple months ago called The ATT Recession, and I tried to bring some quantitative rigour to this question. I focused on the ad platforms, and I sorted them into groups. Here’s a group that would very obviously be impacted by ATT, and here’s a group that wouldn’t. And if you look at the [platforms] that are impacted by ATT, the revenue dropped significantly or the growth dropped significantly. And then the [platforms] not affected by ATT, for the most part, revenue hadn’t changed at all. But a lot of these platforms were not blaming ATT for that, they were blaming macro headwinds.

My point was that they’re deflecting. The reason they don’t want to acknowledge that it’s ATT is because ATT is systemic and permanent, and if they blame it on the business cycle, the assumption is at some point [it] will improve.

But the thing is, it’s a mistake to just look at the platforms and say, ‘Well, Facebook, their revenue is down on a year-over-year basis for the last two quarters. But who cares? Facebook is a big company and they’re not losing money. They’re just going to be less rich.’

Well, no, because all of that lost revenue is advertising spend from essentially SMBs [small-to-medium-sized businesses] that were using these platforms to grow their products. So if there’s a hole in that revenue, it’s from these companies that needed that ad spend to produce revenue. The problem is there’s less public data to support that because no SMBs are public companies. So they’re just sort of invisible.

So what exactly changed for advertisers as a result of ATT in terms of how they buy advertising online?

What changed? Well, the ability to target someone based on their commercial proclivities, based on their behavioural profile – that was a really effective way of targeting people for ads, especially for ecommerce and apps, and any outcome-based advertising.

So if I’m buying revenue [or] I’m buying a conversion, I’m paying an ad platform so that they can source some kind of outcome for me, and that has commercial value. It might not be a purchase, it might be someone registering, it might be someone adding something to cart, it might be someone viewing 10 products in my catalogue. And the ability to know that those things happened was very effective at targeting ads to people.

Essentially, what you had with the system was a giant data co-op. Everyone sent their data back and it got attached to people’s profiles […] and it got sort of pushed into this giant stew. Again, you could make the argument that should never have existed, and I’m not necessarily saying that that’s wrong. But that supported a massive economy, and I think it’s important to acknowledge that and recognise it. And if you do acknowledge that and recognise that, and you still come to the conclusion that society is better off [without it], then fine. I would disagree, but then at least you would have made an informed decision about that.

But I don’t think the ATT pop-up presents consumers with a real choice. All it does is present the downsides. It doesn’t present any of the positive aspects.

Why didn’t the platforms adjust and lower CPMs (cost per thousand impressions) to make up for the lack of targeting?

The platforms don’t set CPMs, that's all decided by an auction [...] The only people that care about CPM are brand advertisers because all they’re really buying are impressions. They don’t care about any sort of down-funnel effects. ATT might have even been a good thing for them because a lot of the direct response advertisers exited the market, or their bids are much lower because there’s less targeting relevancy. But for the direct response advertisers, CPM is not a meaningful metric.

Will the forthcoming deprecation of third-party cookies by Google have a similarly destructive effect on the market?

I don’t think it will be as destructive just given the size of those different markets. There are a couple of characteristics of these separate ecosystems that are important to highlight. My background is in mobile app advertising. So, that primarily happens through big platforms like Facebook, Snap, TikTok. For the most part, those are walled gardens [and] there are safety measures. They’re not 100% effective – scams get through and people get defrauded – but for the most part, there’s oversight.

The open programmatic web is the Wild West. It’s a totally unregulated ecosystem. And if you eliminated a lot of the bad behaviour that happens in the open programmatic web, consumers would not feel any detrimental impact. The only people who would feel any consequences of that are the people that are engaged in it. On the walled garden side, I think that’s just less true.

I think those two ecosystems get conflated as well. So I think it’s important to recognise that distinction. [But] that’s an aside. I kind of forgot the question. I'm sorry.

It was about whether the deprecation of third-party cookies coming up was going to be as disruptive as ATT or wherever you’ve been priced in.

Okay, so that rant was totally irrelevant. It won’t have as material of an economic impact because the open programmatic web is, in terms of advertising expenditures, just smaller than the part of the ecosystem that ATT regulates. But nonetheless the cookie deprecation would have the same magnitude of impact for that sort of applicable portion of the digital advertising market as ATT.

Now, what I think Google’s doing, and what I think explains the delays with cookie deprecation, is they’re trying to replace cookies with something that is as performant but is protective of consumer privacy. If they’re able to do that, that’s an economic miracle.

You’ve also written that ‘everything is an ad network’ (meaning lots of companies are creating their own platforms to sell ad space to brands). Why is that now the case?

My theory is it’s a result of ATT. Facebook was the everything store for ads. Any advertiser could have gone there and advertised because the audience was so big. And Facebook could subdivide that huge audience into very specific sub-audiences that were interested in very specific things. If I wanted to advertise a very niche strategy game, I’d go to Facebook, they’d find among the 2 billion people that use the Facebook app every single day 10 million [people] that are really into strategy games, and I could advertise directly to them. Or if I was selling hammers, or I was selling unicycles, they would find those sub-audiences that were very relevant. It was basically a discovery mechanism on humanity scale for commercial interest.

Photo by Filios Sazeides on Unsplash

When you lose that, those people that were advertising unicycles, where are they gonna go? They’re going to go to the company that sells unicycles that, all of a sudden, just created an ad network. Because if you want to reach people that are interested in unicycles, they’re the only people that have that data as first-party data.

So what the unicycle retailer woke up to one day was, ‘Hey, you know what? We’re the online shop that everyone goes to if they want to buy a unicycle. Every single unicycle we’ve sold, we know that the person that bought it buys unicycles, and we have all their data […] You can’t go to Facebook anymore because they don’t know who’s buying unicycles because that transmission mechanism is broken. Well, we do. Every single person that buys anything from us is a unicycle fan because that’s all we sell. So we’ll create an ad network, and you can buy ads on our website.’

When you don’t have behavioural history, then you go to contextual relevance. If I’m selling something, I go to the retailer or whatever outlet has contextual relevance. And then all of a sudden those companies woke up and they said, ‘We could make money. We have this data, we can monetise it, just by layering an ad network. Before we couldn’t compete with Facebook, no one’s going to advertise with us relative to Facebook because every advertiser is already on Facebook, and people don’t want to integrate a new ad channel.’ But now the unicycle retailer can’t go to Facebook because Facebook can’t find the relevant audience. So they just create an ad network, and they instantly create a brand new revenue stream that is derived completely from the data that they already had.

Photo by Joshua Earle on Unsplash

What do you see happening next as a result of the changed online advertising landscape?

I think the problem with most companies that are dependent on digital advertising is that they see it as their primary growth driver for revenue but they don’t understand it. And I think what I overestimated going into ATT – and all these other beats that are going to happen that restrict the ability to do targeted ads – was that these companies understood how critical that this practice was in driving profitable revenue growth. But most didn’t because they see advertising as some ancillary activity. Their core focus is building whatever product they build. And so my sense was people would wake up to the potential threat of ATT earlier than they did and that they would adapt to it and build new technologies and new strategies earlier than they did.

So what happened was ATT got rolled out and people had no idea how it impacts their business, and then they had no idea how to adapt. So what you’re seeing now I think, finally, is this recognition [that] this happened. You could have gone through the stages of loss or whatever, but hopefully you’ve arrived at the seventh stage and you’ve reached acceptance, and hopefully you’ve activated whatever strategy you had to to overcome that.

And I think what most people are realising is that it was sort of an albatross around their neck, the total dependency on targeted digital ads. And when you break free of that, the whole world is your billboard, right? I can go and I can get influencers on YouTube, I can buy literal billboards, I could run TV ads, I could buy radio ads, I could do all this stuff. The limitation was I made myself totally dependent on Facebook's infrastructure. No one forced that upon me, that wasn't the only way to advertise, that was the easiest way to advertise.

But if I build the statistical methods to try to attribute the conversions that I see in my system with the ad spend that I’m placing all over, then I have the total freedom to advertise in whatever way I want. And I can discover the ways that are most effective for me. So that’s an optimistic way to look at it.

Some companies will never be able to build those systems, and it’s gonna take a long time for SAAS [software as a service] platforms to evolve that can do that really well on their behalf. But it’ll happen, and when it does, I think it’s a really promising future for advertising broadly.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.