Fred Pelard on how to be strategic /

Former rocket scientist Fred Pelard believes anyone can learn to be strategic. He tells us how to build the intellectual muscle groups that will help you solve problems and make better decisions

Chloe Markowicz

/

How can people get better at strategic thinking? Fred Pelard, a trained rocket scientist and former Deloitte management consultant who has 20 years’ experience teaching strategic thinking to executives across organisations from Diageo to Nike, has the answer. His new book How to be Strategic promises to explain ‘everything you need to know to think strategically in any situation’. Drawing on expertise including Chan Kim’s Happy Line framework, Eric Ries’ Lean Startup and Barbara Minto’s The Pyramid Principle, the book outlines the necessary mindset and tools to achieve superior strategic thinking. Described as ‘a must-read for everyone who ever deals with complex important challenges’ by Richard Rumelt (the author of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy), Pelard’s book explains how to come up with great ideas quickly, eliminate undesirable options and convince key stakeholders to buy into your decisions.

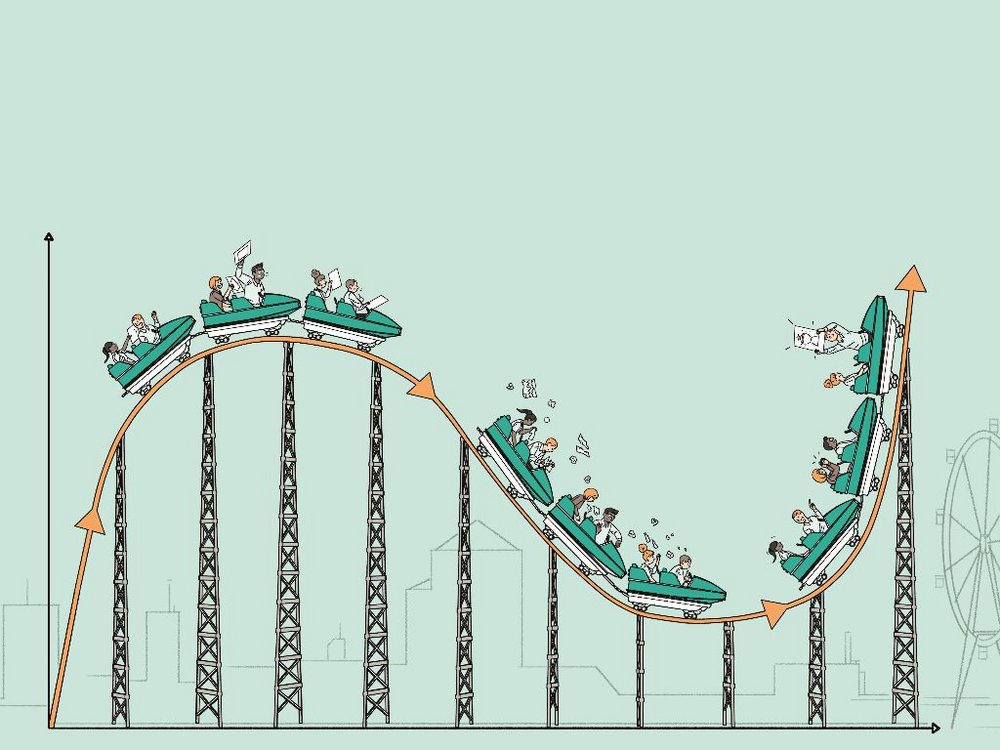

Here, Contagious speaks with the author to find out more about his ‘rollercoaster of strategic thinking’ approach and why it’s the best model for working smarter, not harder. He also sets out ways that people can be more strategic and warns why data is the biggest trap.

How do you define strategy? And what exactly is the difference between strategy and strategic thinking?

Corporate strategy is: where should your organisation deploy resources over the next three to five years? Brand strategy is: what’s the best way to get this brand to succeed over the next few years? Strategic thinking is waking up every morning and going: ‘Right, what’s the most important thing I can do today?’ Brand strategy or corporate strategy is about applying a big chunk of thinking to a really big, infrequent problem. Strategic thinking is actually using very similar intellectual muscle groups applied to all sorts of problems all the time. So there are lots of slightly smaller scale questions that are not what people would commonly refer to as the strategy. But they’re quite strategic to the outcome.

How is looking at a problem strategically different from other ways of thinking about it?

There are four ways to solve problems: the expert mode, the analytical mode, the creative mode and the strategic mode. An adult gets dressed automatically; they’re experts at getting dressed. But, with a small child, they can choose to get dressed in very creative ways. One day, they’ll try and put their socks on their ear, and then the next day, they’ll put a shoe on the wrong foot. That is a very creative, exploratory way to discover how to solve a problem. The expert mode is: I already know the answer, I will do it the way I know how to do it. The more creative approach to solving problems is to try and invent solutions. That’s what you see a lot in advertising and marketing.

Fred Pelard

What I see a lot in other parts of the business – typically operations, finance, or tech – when people don’t know the default approach, they to go into analytical mode. They give me lots of data, because when I have lots of information, then I will be able to deduce the answer. One of the things I’ve seen in corporate organisations is the battle of temperaments between people who default towards the creative approach to solving problems versus people who default towards the analytical approach to solving problems. What we see in agencies and marketing now is one of the things that happens when you bring analytics into the brand strategy process. Not only is it a different type of tool, but it’s also a tool that you use at a very different sort of core temperature.

If a problem is really strategic, the answer to it lies in the future. With a lot of other professions, whether it’s lawyers, investigative journalists, accountants, HR, etc, a lot of the answers to their questions lie in the past. You know, if you think about the heart of HR, it’s performance reviews.

When something is strategic, you’ve got to first invent solutions for it because it’s in the future and you won’t find any data on it. You can’t analyse the future. You can say that in a nutshell, strategic [thinking] = creative [thinking] plus analytical [thinking]. From my experience, talking to planners in the brand strategy world, there is this idea that you bring the planners and they seed the ground for the creatives to deliver a beautiful, creative answer to a brief that’s been analysed well. In the corporate strategy world, you have to use the same two weapons slightly differently, in the opposite order. So, you’ve got to invent the future, and then analyse it to find that answer. If you asked a creative agency, for example, to create a great campaign for Contagious, their first step would be to talk to you in great detail about what is it you do exactly. They would gather lots of data and then the creative would have a flash of inspiration about selling Contagious. If you asked someone in corporate strategy, their first step would be to ask, ‘What should Contagious be doing over the next five years?‘

How can you get better at strategic thinking?

It’s the equivalent of learning a new sport. You can break down the strategic thinking approach into a series of skills. One of the skills is to structure any problems. There is a lady called Barbara Minto, who was the very first female consultant hired by McKinsey. She was very good at being emotionally intelligent in a world of slightly stiff men, the extra skill she brought is that she understood that many of these men would tackle problems by saying things like, ‘How can we be more successful?’ or ‘What should this organisation do?’ If you approach problems with questions to which you don’t have the answer, because you’re not an expert and the question is in the future, your brain can keep sending you micro waves of ‘I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know.’ And, actually, asking lots of questions, which is what many strategists do, actually slows down your ability to solve problems. Barbara Minto reframed problems. So instead of asking yourself, ‘How do we sell more chairs?’ for instance, she says, ‘We’re selling way more chairs in 2023.’ And then she asks, ‘What do we need to do for that to be true?’ And that tiny mental trick, where instead of carrying a question in your mind, you’re reframing the problem to a successful outcome, usually that elicits a smile from the person who’s done the flip. Once you flip from a question to an outcome, once you have visualised the outcome you desire, you work backwards and go, ‘What do we need to do for this to be true?’

One of the things you talk about in your book is the ‘Up, Down, Push’ approach. Can you explain this?

In the book, I talk about a rollercoaster of strategic thinking. For reasons of gravity, a rollercoaster always starts by going up.

In a business context, it means first be creative, invent lots of possible solutions to your problems. But if you stay at that level, you’ll never really land an outcome. So once you have lots of ideas, you start going down the rollercoaster. And the best way to go down the rollercoaster is to start coming up with reasons why some of your ideas won’t work.

Fred Pelard

In the early stage, when you go up, you’re filled with enthusiasm. There was a really interesting moment during the first Covid lockdown where after a few weeks of depression for most people, they started thinking about all the things they could be doing: I could learn a language, I could redo my bedroom. Everyone felt really up. Then what happened? People eliminated the ideas one by one because they had limited resources. So I can’t learn to play the saxophone, and paint and learn a new language. Eliminating these things feels like it’s a downward expression.

Once you decide which is the best thing for you to do, then you need to convince lots of other people. So that’s the push, to convince stakeholders that the option you’re going to execute is the right one. And they should help you either by harnessing internal resources, if it’s a B2B situation, or by coming to buy your product or service, if it’s a B2C situation.

How do you convince key stakeholders to get on board with your decision and come along for the ride?

There are four ways that people receive information: they can see it, hear it, feel it or analyse it. The advertising industry in particular is brilliant at visuals and emotion. And so it develops a way to convince your end consumer to buy the product or service. Another big stakeholder you’ve got to convince is the rest of the organisation, whether it’s your supply chain or finance department.

Advertising agencies should be trying to convince consumers using visuals and emotions, and internal stakeholders have to be convinced using words and numbers. It’s really as simple as that. Pictures, words, emotions and numbers are diverse languages the way German, English, Spanish or French might be. Ad agencies might be monoglots when they should be polyglots. They tend to recruit and develop people who are really good at speaking certain type of languages. It’s the equivalent of recruiting people who only speak Spanish and then being puzzled at the fact that Germans don’t understand what you’re saying.

People in the creative industries are strong at convincing the consumer, because they’re great at falling back on visuals and emotions. But these two languages tend to leave corporate types cold when they’re at work. Those same corporate types might shed a tear at an ad, but when they’re at work and you’re trying to convince them to invest in something then they want to be convinced through other media.

What do you need to do to be more strategic in your day-to-day life and work?

If you look at people like Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, everyone who has worked with them says, one, they’re brilliant, two, they’re impossible human beings. I’m not suggesting that people should become psychopaths to become strategic, it’s the other way around. People who are really strategic don’t differentiate between building up an idea and tearing it down. They think of it as part of the same rollercoaster. When Elon Musk says Bitcoin is the future of the world, he really means it. When three days later he says Bitcoin will never work, it’s still part of the same logic where you explore your options (you go up) and then you go down.

One of the big traits of strategists is that they are equally attuned to the optimistic nature of wild ideas that could work and then a nanosecond later, or a day later, they shift to ruthlessly eliminating the ideas that will not make it all the way to the end line. In doing that, often they rub people the wrong way.

I work with a lot of strategists and people who have that skill and for them the next step is to use a velvet glove of emotional intelligence, to recognise that not everyone enjoys the whiplash of being manically optimistic one day and depressingly realistic the next as a way to get to the right outcome. The way to build that skill is for you yourself to take the counterpoint of your position on any given idea. If your natural inclination is to think, ‘This is not going to work,’ then ask, ‘What would it take for this idea to work?’ If on the other hand you’re very enthusiastic about a business idea, then the best way to be strategic is for you to go, ‘What would it take for this venture to fail?’ By doing this you’re sharpening your sword and your ability to invent new solutions and take down the bad ones, so that what’s left is the best outcome.

What’s the biggest trap when it comes to strategic thinking?

The main 21st-century trap is this perception that everything is about data. Interestingly, the people who know about data don’t fall in that trap the way that people who don’t know about data do.

Now, there are lots of people at the top of organisations who want to force AI or data into the strategic thinking, and what it does is delay the point at which you start thinking because you have to wait for the data.

The biggest hurdle to people thinking strategically in the 21st century is that you need data to have ideas, and that’s not true. You need data to have solutions. But you don’t need data to have ideas. A solution is an idea that has survived contact with data. Of course sometimes data can help you have ideas, but so can madness. There’s a history of mad people being quite inventive, but we don’t say you have to be mad before you invent things.

Too many people wait for the data to show up before they engage their strategic muscles. That data either never shows up or shows up in ways that are too hard to read and you’ve wasted time.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.