Why high fashion brands don’t have the luxury of ‘eating the rich’ /

Global growth means luxury brands have a larger pool of customers than ever before, argues Oskar Zander, a client manager and digital strategist at TBS Mediabyra in Stockholm, and that could be their undoing.

Photo by Dima Pechurin on Unsplash

In November 2022, Gucci stunned the world of fashion by announcing it was parting with its superstar chief designer, Alessandro Michele. While some insiders welcomed the move as forward-looking, others questioned what more Gucci could possibly want — Michele had helped Gucci triple sales and quadruple profits since his debut in 2015.

But Gucci was hit hard by the pandemic, harder than many of its competitors. Revenue at Gucci declined 14% the same quarter that Michele’s exit was announced.

Rising interest rates and a slowing global economy have since kept growth sluggish within the luxury industry, and the middle-class western customers that flocked to luxury brands during the boom years are now spending less on designer gear.

Gucci recently hired Alessandro Michele’s replacement, Sabato De Sarno, an experienced-but-relatively-unknown designer with stints at Valentino and Prada.

Whether or not De Sarno can reverse the fortunes of the company, the Gucci saga raises some important issues about the marketing and branding mechanics of luxury labels.

For instance, what makes a luxury brand desirable and profitable? And how do you balance those two ends in a difficult business climate like today’s?

In a recent article for Contagious, Weber Shandwick’s global chief creative officer, Tom Beckman, called for a more accessible version of luxury. Instead of targeting the obnoxiously wealthy few, he argued, high fashion brands must now make sure that everyone can relate to and afford their products. Only by doing so can they thrive and avoid being relegated to history’s dustbin as old-fashioned symbols of vanity and greed.

I think it’s the other way around. And Gucci shows why accessibility can be a risk for luxury brands.

Right now things are not looking good for friends of freedom, democracy, and prosperity, but zoom out a little and the picture is more encouraging.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of millions of people have been enriched by globalisation. Despite the shock of the pandemic, the share of the world’s population living in extreme poverty is now at its lowest ever level — 8.4 % compared to 27.8 % in 2000.

Much of the progress has been thanks to China’s economic progress. In the 1960’s, while Gucci rose to fame in the western with its Jackie bag, Flora scarf and Double-G logo, China was one of the world’s poorest countries.

But reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 led to 10% annual growth rates for nearly 30 years, reducing the share of the population living in extreme poverty from 88.1% in 1981 to 0.2% in 2019. Now, the Chinese are queuing up to buy not bread but Balenciaga.

All of which means that luxury brands now have a larger pool of potential customers than any other time in history. And while the expanding global middle class has been great for luxury brands’ short-term growth, it could also upend the very nature of luxury.

The market economy has lifted great swathes of people into relative comfort. And because so many of us seldom need to worry about feeding our children or avoiding malaria, we are free to move up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and dream bigger, about things just out of reach.

Luxury brands thrive on those aspirations and that unspoken promise of a better version of you. They don’t solve a problem; no one needs a Gucci buckle belt. But buying one feels good, and it contributes to the image we want to project.

That’s how luxury marketing works, and that’s why brands like Gucci target lots of people and not just those that can afford them. There’s little point buying a designer brand unless other people know what it means.

The same mechanism applies to most other categories and products, regardless of what they cost or communicate. Every time we buy something, we make a statement, provided everyone else is getting the same message.

Look at what Oatly did with oat milk. They attached a semi-political purpose to a rather boring product, and suddenly you could express an entire lifestyle by ditching the cow milk that everyone else was drinking.

The problem with those radical statements of values and preferences is that they lose potency as more people adopt them. Being a rebel isn’t fun if no one objects. Drinking oats says nothing exciting about you if everyone else is doing it, too.

By the same token, when everyone can afford a luxury, it ceases to be a luxury. Marketing luxury brands is therefore about those that can’t afford them almost as much as it is about those that can. It’s not for everyone, and everyone also needs to know that.

And it never stops because people never stop aspiring, and that is what both feeds and threatens the luxury fashion industry in the long run.

‘Fashion fades’, said Yves Saint Laurent, ‘style is eternal.’

That is why some luxury brands rise quickly only to slowly lose steam, while others stay relevant through downturns and shifts in taste.

Designers like Michele at Gucci, Demna Gvalsalia at Balenciaga and Riccardo Tisci at Givenchy all created desirable brands with distinctive characteristics, but eventually their visions stagnated commercially.

Some of this is just a case of fashions fading. But I think there’s also something else going on. These brands had such distinctive styles and were so successfully marketed that everyone could recognise them and understand what they meant as symbols.

So, as more people were lifted into the global middle class, they flocked to these brands, to the extent that they lost some of their exclusive meaning. It’s like drinking oats: an exciting statement when no one else does it but dull and predictable when you’re one amongst millions.

The same flare that characterised Alessandro Michele’s Gucci and propelled the brand forward also contributed to its stagnation. It simply became too accessible.

So how can luxury brands maintain exclusivity as a growing global economy enables more people to not just fantasise about them but also afford them?

Again, I believe Gucci is instructive.

The success of some fashion labels is driven by designers, for others it’s the brand. The latter tend to be underpinned by a timeless aura and a focus on quality rather than innovation.

Hermès and Dior fall into that category: recognisable but not oversaturated, and faithful to certain aesthetics regardless of market preferences.

They’re still aspirational but on a different level to the fashion-driven house. They are also generally more expensive and cater to even wealthier people.

According to Bain, 2% of luxury customers drive 40% of luxury sales. Those consumers are less likely to be affected by changes in fashion and are less sensitive to recessions, providing consistent growth and profits to the brands that serve them.

Gucci started like this and was known for quality leather goods under the tagline, ‘Quality is remembered long after price is forgotten’.

But as the business grew and garnered endorsements from stars like Grace Kelly and Sophia Loren, Gucci was lured by the appeal of a broader market into mass-production, diminishing its exclusivity.

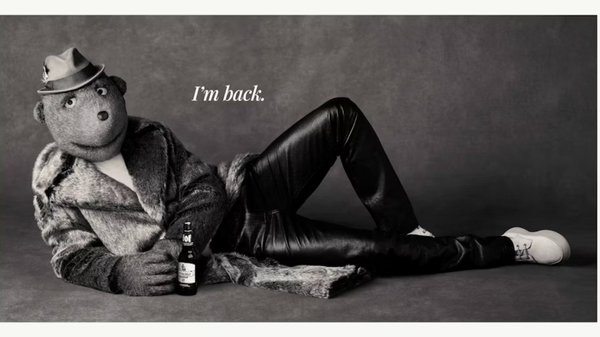

In the early 1990’s, a new strategy was devised. The number of stores and products was reduced, and Tom Ford was hired as chief designer. His porno chic aesthetic — alongside a substantial price-hike — revitalised the brand. But it also planted the seeds of its present troubles.

Ironically, in 2005 Ford launched his own brand, which is characterised by that timeless quality of quiet luxury and delivers consistent sales by catering less to the masses and more to that top 2% of buyers.

Photo by Herman Delgado on Unsplash

The challenge for fashion-driven luxury brands like Gucci is clear: They need to be relevant but not so accessible that it dilutes their appeal.

Simply raising prices isn’t enough. And you don’t attract the 2% who account for almost half of luxury spending by caring what the masses think is fashionable, or with ad campaigns signalling aspiration. The exclusivity of these high-end brands is achieved through consistent, long-term strategies that communicate their timelessness and alluring quality.

And that might be the slightly disappointing conclusion. Not everyone can do what Dior and Hermès does. There are no shortcuts; such reputations are built on entire backlogs, and once devalued it’s difficult to climb back up. And it becomes even more difficult with each day that passes that creates more aspiring luxury customers.

Only one thing is sure: at whatever rung of the ladder the growing global middle classes reach, there will be brands ready to meet them.

At the top of that ladder stand the truly exclusive luxury brands, above the economic turmoil and vicissitudes of fashion.

Eating the rich might seem like a radically interesting and even profitable concept in times of economic downturn and social unrest, but for luxury brands that would mean biting the hands that feed them.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.