The ‘wiggle room’ in marketing science /

Do the laws of marketing science laid down by the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute leave wiggle room for creativity to play a role? Ethan Decker, president of Applied Brand Science, explores.

Contagious Contributor

/

Photo by Ramón Salinero on Unsplash

Ten years ago, Byron Sharp started a small brush fire with a little book called How Brands Grow. It wasn’t supposed to be a hit. It was just a slim summary of ideas that built on Andrew Ehrenberg’s research dating back 60 years. But it blew up, because it seemed to blow up some sacred beliefs about brand building.

Brands aren’t emotionally differentiated in consumers’ minds, he concluded; they’re basically interchangeable. Brands must fight for the same people; the Coke drinker isn’t any different than the Pepsi drinker. Advertising doesn’t persuade; it mostly refreshes memories. The book said this and more.

Since then, nearly everybody in the industry has lined up on one side or the other with Byron Sharp and what have become known as the Ehrenberg-Bass laws of brands (named after the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute at the University of South Australia). There have been pissing matches about who knows more about branding: a bunch of egghead academics, or people in the trenches actually working at brands? Marketing people describe themselves as ‘pro’ Ehrenberg-Bass or ‘anti’. There have even been public debates: is Ehrenberg-Bass brilliant or bogus? Truth or treason?

Ethan Decker, Applied Brand Science

Underneath this debate is fear. In particular, it’s the fear that if there are scientific laws of marketing, pretty soon the scientists will finish the job that the quants and bean-counters started, and wipe out the space for creativity. After all, laws are things you can’t break, like the force of gravity or the speed of light. There’s no room for creativity. Marketing becomes predictable, mechanical, lifeless.

But this isn’t the case. Far from it, in fact.

Take the double jeopardy law. It says that small brands suffer twice: they have fewer buyers, and those buyers buy less often. In other words, small brands have lower penetration and lower loyalty. In the US, Mini sells fewer cars to fewer people than Ford. And despite what people say about the passionate Mini fan base, Mini owners come back for another Mini only 30% of the time. Meanwhile, 54% of Ford owners buy another Ford.

The double jeopardy law holds in every category ever studied, from toothpaste to luxury watches, from credit cards to aeroplane seats – and even the aircraft themselves.

However, there’s wiggle in the numbers. Sometimes a lot. Porsche sells fewer cars than Volvo, but its repeat purchase rate is a third higher. And Subaru, which sold just a quarter of the cars Ford did, had a repurchase rate of 62%. That’s much higher than Ford’s, and way higher than the 45% that the law predicted.

The eggheads often pooh-pooh the wiggle as minor deviations and outliers. The patterns still hold! The laws are universal! True. But the wiggle adds up to real money over time. Subaru went 93 consecutive months with year-over-year sales increases and has grown fourfold from 2002 to 2020. Does this mean Subaru has broken the double jeopardy law? Is Subaru somehow defying gravity? No. It just means the laws don’t account for everything that happens in the real world.

Another law-like pattern is that most people see most brands as fairly interchangeable. For instance, Sharp shows that only 25% of Apple users think the brand is unique compared to other computer brands. Only 25%! For one of the strongest brands in the world! That’s demoralising if you hold tightly to the belief in pervasive brand love. It’s also jarring if all you see in your mind are fanboys camping out on the sidewalk for new iPhones.

However, even though ‘only’ 25% of Apple’s customers think the brand is unique, that’s double the average for other computer makers. You’d have to be daft to think this minor deviation doesn’t contribute to their major profit margins and business results.

How do you create wiggle or become an outlier? Certainly by doing lots of little things a bit better than your competitors. Apple and Subaru both have focused product lines, build quality products and create great retail experiences. But you also create wiggle by being more creative and doing things your competitors didn’t even dream of. Subaru and Apple have run brave, distinct and creative brand marketing campaigns for decades.

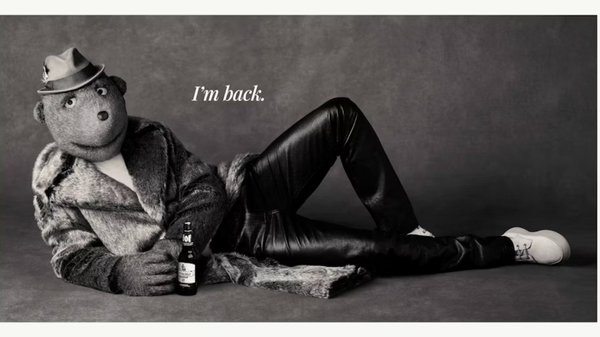

Further, the Ehrenberg-Bass laws don’t tell you what creative solutions to use, nor what their effect will be. For instance, the semi-truck category follows the same laws as cars and computers: small brands have fewer buyers who are less loyal, and most people see the brands as more similar than different. Let’s say you’re middle-of-the-pack Volvo, and you’ve developed some great products with advanced technology, like precision steering. If you want to find some wiggle, do you just print lots of brochures and film some normal product demos? Oh no. No, no, no. You get Jean-Claude Van Damme to do a split between two trucks. At sunrise. While they drive backwards. To the blissful sound of Enya. That’s how you bust the curve.

So don’t fear the marketing science. It might be disheartening that brands are a lot less special — and people are much less into them — than we wish. It might be weird to think so much of your brand dynamics are predictable and constrained by these laws. But the wiggle shows that there is still space for the unpredictable. And that creativity is a mighty lever to help brands defy expectations and, if only for a little while, soar.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.