Karen Nelson-Field on attention, ad-fraud and a looming ad-tech crash /

Media and marketing expert Professor Karen Nelson-Field’s new book pulls no punches when it comes to the advertising myths that marketers hold dear. The author talks to Phoebe O’Connell

Phoebe O’Connell

/

This article was first published in issue 62 of Contagious Magazine.

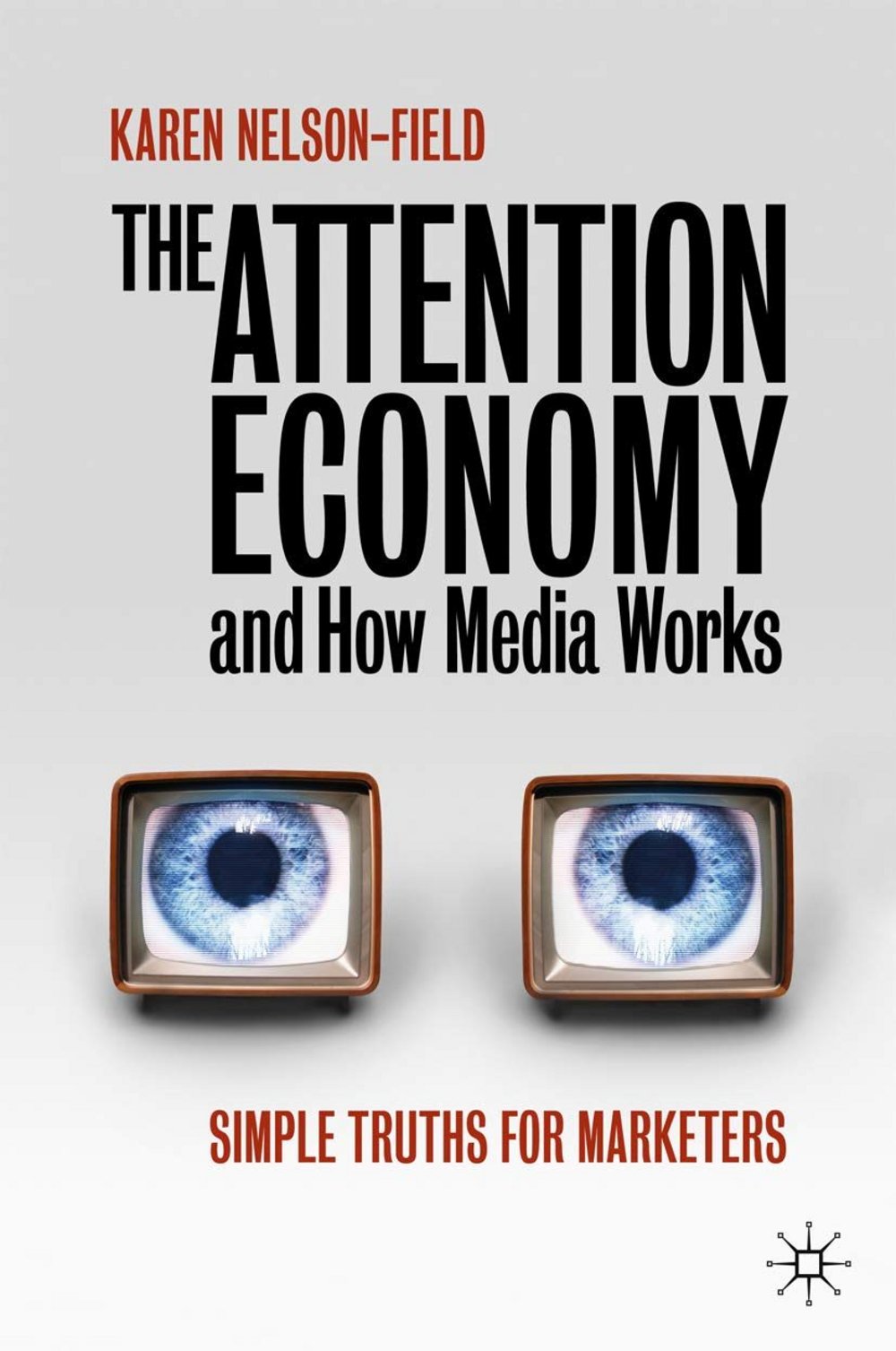

For the past few years, media strategy expert Professor Karen Nelson-Field and a team of PhD-trained marketing researchers and computer science engineers have been building a rigorous and technologically driven research process to measure marketing effectiveness.

As a University of Adelaide professor, author and former research associate at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, Nelson-Field’s research into social media marketing, video sharing and the measurement of attention has made her a global authority on media strategy.

In 2016 she founded Amplified Intelligence, a research consultancy group in Adelaide, Australia, where marketing research design meets machine learning. ‘The organisation was born out of frustration with an over-reliance on surveys and the need to move faster than the university system would allow,’ Nelson-Field tells Contagious.

Now Amplified Intelligence’s research into the media strategy that drives brand growth has come to fruition in Nelson-Field’s latest book, The Attention Economy and How Media Works: Simple Truths for Marketers. As in her previous book, Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing, Nelson-Field targets ‘viral’ myths, urges us to seek out more rigorous research and offers a thorough, unflinching assessment of our industry, and the falsehoods and missteps that endure.

As Nelson-Field puts it, in an era of ‘fake news and fast facts’ our attention is evermore divided – but what does that mean for marketers? In The Attention Economy she outlines a recipe for better media research, argues for the merits of distinctiveness over differentiation, and explores the two types of attention and how they impact sales.

Alongside these truths are warnings that marketers ignore at their peril: the insidious nature of ad fraud, the shortsightedness of instant measurement, and the inevitable ad tech crash.

Contagious spoke to Nelson-Field to find out how the currency of attention is set to shape the state of marketing.

What is the biggest mistake that marketers make today?

You might think that I would say: ‘You’re not thinking about your long-term brand growth.’ But I think that’s been addressed. What lies below the surface is the digital space – the scale of fraud that sits behind the digital marketplace is unbelievable. I feel like that’s one of those things that marketers just don’t want to know about.

There are a few really smart brands that have some real boundaries around what they buy and how they know what’s human or not, or duplicated accounts, but the majority of brands, a lot of their advertising is wasted because it’s not being seen [by humans but by bots]. The second part of that is the visibility issue. But that’s at least on the surface.

With the human element, it’s hard to know. I think people underestimate [ad fraud]. What is the biggest mistake? It’s being a little naive to the reality of what you’re buying. There are things you can do to improve your odds. The programmatic marketplace is rife with ad fraud, so speak to your media buyer and try to work out a system to improve the human element.

What can we expect to learn in your latest work?

The main theme is what you can do to maximise attention when we live in a world where the majority of us walk around in a subconscious state – we don’t pay a lot of attention generally, let alone to advertising. The book is about the sorts of things advertisers can do to improve their odds. It’s about what the industry can do as a whole to improve the effectiveness of advertising. For example, I speak about my intolerance for less than 100% pixels on screen [pixels being how much of an ad appears on screen], because we can see without a doubt that that makes a massive difference to both sales and attention. The book explores the reasons why attention moves in and out.

There’s a real push for currency reform. At the moment, impressions and the way that we buy media is based on a very impure product and it’s not comparable cross-platform, so tension is definitely rising to the fore in terms of attention being a currency option for future trading.

Professor Karen Nelson-Field, University of Adelaide

Why write this book now?

We didn’t expect [Amplified Intelligence’s research gathering] technology to be as solid as it was or is, but we’ve now done enough work over the past three years to have enough findings in the attention space [for the book]. Originally, we were looking at cross-platform advertising effectiveness, but then when you start to uncover which platforms are more effective, there are obviously questions around why that is and so the attention piece comes into it. Why do you pay more or less attention to certain platforms? We had all of these findings coming out of the core composition of the research.

Do you think attention should be an alternative metric?

I’m not the first to suggest it – [planning and media buying agency] PHD Global was talking about the importance of attention and the attention currency several years ago – but I’m definitely a loud voice right now. Everyone’s so frustrated with the nature of how media is bought and sold now. There’s a real push for currency reform. At the moment, impressions and the way that we buy media is based on a very impure product and it’s not comparable cross-platform, so tension is definitely rising to the fore in terms of attention being a currency option for future trading.

As in your book ‘Viral Marketing: The Science of Sharing’, you touch again on the term ‘viral’. Is it a term that’s still misused?

People are more aware of the concept that there’s no free lunch and are starting to get that there is a lot more investment that sits behind media now. We’re not just trying to ‘suck it and see’ and hope that we earn reach. Most people get that viral is not quite the big thing that everyone put it up on a pedestal to be, so that’s kind of a big change. I still included it in the book because it’s a really important point to make. If you want your advertising to be successful, you can’t rely on the algorithmic editor of Facebook.

The focus on ‘going viral’ seems to be a symptom of short-termism. Why do you think marketers are so obsessed with short-term measurement?

That’s [marketing effectiveness experts] Les Binet and Peter Field’s area, but the book sets up the context of the past 15 years of this seismic change in our industry. Why are brands obsessed with instant measurement? Because you can see an instant result. Everything’s instant, people want to know in real-time whether something works or not and, if it doesn’t, they want to move on.

With the digital granularity in that space you have access to click-through rates or engagement or Likes or followers or fans or whatever it might be. The obsession with instant measurement has been brought about by the nature of the commercial models that sit behind these platforms. There is nothing like that on TV yet. TV has been slow to move into this instant effectiveness space – and probably rightly so, because it means that campaigns get switched out much quicker and focus on heavy buyers of brands.

How does short-termism impact what you refer to in the book as ‘factfulness’?

That comes from the book Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling. It talks about this concept of how, as humans, we always think, ‘In the 1970s, it was so much easier, or in the 1980s it was so much more fun or free.’ Rosling says that humans forget and live in bubbles and then only operate in the world that they live in right at that very moment.

That’s kind of the same in the advertising space: if you’re only sold the concept of click-through rates and you don’t look at the bigger picture, then you flock towards that. We live in this constant state of ‘factfulness’ around media buying. What, in practice, makes that a dangerous behaviour for advertisers? It means that brands over-focus on heavy buyers, they focus on short-termism. They’re not really looking at the long-term game. Most CMOs last what, two, three years? The brands that have stood the test of time have been around for hundreds of years. So in practice, it’s bad news for long-term brand growth.

When you see patterns pop up in a lot of places – in different time zones or in different categories or in different countries – that’s when you know there’s actually something there and it’s not just a fluke.

Professor Nelson-Field

What’s stopping advertisers from focusing on longer-term measurement?

It’s expensive!

It comes down purely to cost?

Yes, good metrics are hard to measure, so it’s expensive. It’s really that simple.

Has it always been that way or is short-term thinking a symptom of the increased pressure on agencies and CMOs in more recent years?

It’s a combination of long-term measures being expensive but also platforms having done an amazing job at marketing their own commercial opportunities. The platforms that sell these measures have the money to sell these measures. In the past 15 years, all the digital platforms whose currency is click-through rate or scroll speed or whatever, they’ve sold them as metrics without any empirical background.

In this book you dedicate a chapter to what makes good research. Could you elaborate on why replication is the key to rigour?

For my PhD I was trained at Ehrenberg-Bass, where the whole recipe for good research is around generalisation: it’s about identifying similarities among multiple sets of data rather than significance in any one set of data. When you see patterns pop up in a lot of places – in different time zones or in different categories or in different countries – that’s when you know there’s actually something there and it’s not just a fluke that you found a significant result in one set of data.

With the prevalence of fake news and misinformation, do you think our willingness to take unreliable research at face value is a sign of the times?

Yes. [Advertising results] are not regulated, right? If you’re in the medical field, it takes seven years of testing before the FDA will give you approval. In our field, it’s just selling stuff, so there’s no [consistent] regulation. People want to be able to promote quick results: ‘I found a result here and I’m not going to spend the next two years of my life on this. We’ve found it, we’ll go to market, we’ll move on.’

What do you mean when you say that advertising is not persuasive?

We know that there are statistical regularities that sit behind sales or brand choice. The nature of these laws of growth and the regularities that can be seen within them shows that we are not loyal to a particular brand, we are loyal to many. On top of that, advertising isn’t going to necessarily make us switch brands. Advertising is not persuasive.

The literature shows that advertising is not the formidable force that most people say it is. You have a repertoire of brands, you’re pretty much habitual in your buying and you’re not likely to jump up out of your seat, run off and buy something different just because it’s on TV. There’s a lot of research that sits behind that going back to the 1950s. And it has been replicated.

The general rule is that advertising nudges what you were already going to buy anyway and perhaps gets you to trial something. So this concept that advertising is weak or strong is perhaps not the best way to look at it. Advertising is there to remind you that it’s in the category, but it’s not necessarily going to make you change your mind.

The book also touches on why brands should be wary of prioritising loyalty over growth.

If you want to grow market share, there’s a larger proportion of light buyers that you can potentially get to switch, even once a year. When you’ve got lots of people and a small number of them buy one more time, it has the ability to grow the brand. Whereas there are very few heavy buyers relative to the number of light buyers.

As you say in the book’s conclusion, ‘There is no denying the scale of transformation heading our way […] The changes we are about to see will be a fundamental disruption to the way in which we buy and sell things.’ What does the future hold for the industry?

This is probably a little controversial because I feel like we’ve relied on the work that’s been around for 50 to 60 years plus, but I think there’s change coming. A lot of people are predicting this, but I see that there’s going to be an ad tech crash and the rise of the ecommerce giants will change the nature of the rules that sit behind consumer behaviours. People should be quite interested in how you operate as a brand in 2030, because things are going to be different.

Marketing science advocates will say, ‘No, no, no, it hasn’t changed for 50 to 60 years, so it’s never going to change.’ That’s not right. Our industry has never seen such significant change. The nature of advertising algorithms – which are designed to curate our personal taste, meaning consumers will be exposed to fewer products – will change the way we buy. There will be less chance and it will be more targeted.

To subscribe to our quarterly publication, which is filled with the most creative ideas and sharpest insights from the world of marketing and beyond, click here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.