Why marketers are wrong to dismiss priming /

Decoded author Phil Barden explains why the psychological phenomenon of priming still has value for marketers

James Swift

/

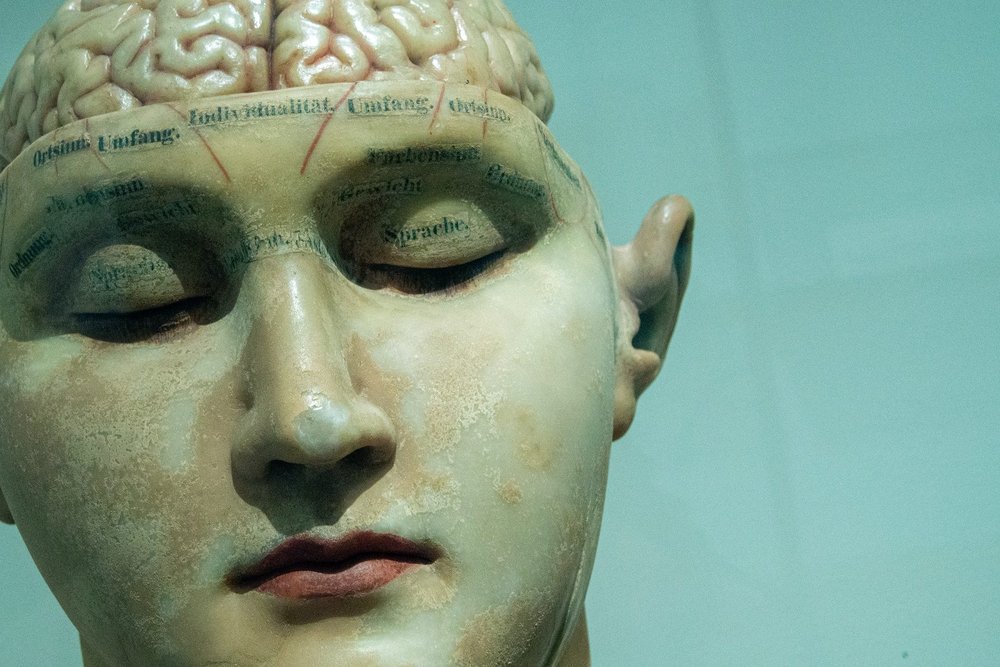

Photo by David Matos on Unsplash

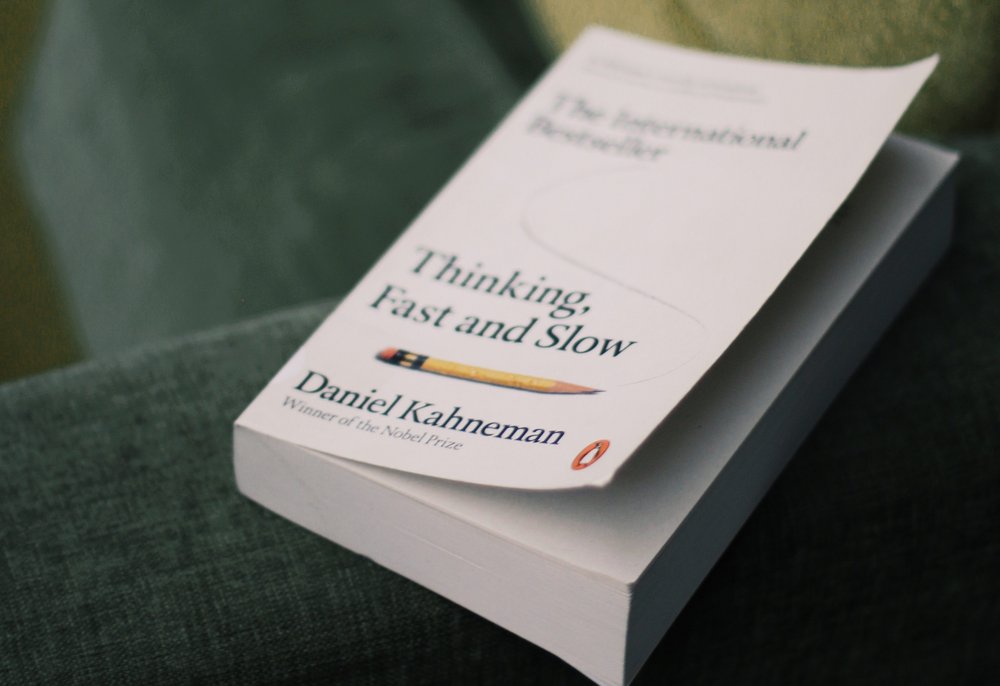

Nobel-prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s declaration last month that behavioural priming research is ‘dead’ prompted a discussion on Twitter about whether the psychological phenomenon should be stricken from marketing theory.

In his 2011 book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman was unequivocal about the validity of behavioural priming research, including an experiment that claimed subjects walked more slowly after being exposed to words related to old age, such as ‘bald’, ‘wrinkle’ and ‘Florida’.

But the Florida study, and many others like it, were discredited when researchers failed to replicate their results, and Kahneman admitted in 2017 that he had ‘placed too much faith in underpowered studies’.

In a lecture for Edge on Adversarial Collaboration published on 24 February, Kahneman reaffirmed his position, disavowing the priming studies (without changing his view on how the mind works) and saying ‘behavioural priming research is effectively dead’ because it has fallen out of fashion within the scientific community.

Photo by Mukul Joshi on Unsplash

Does this mean models and strategies that invoke priming to explain how marketing nudges consumers towards purchases or makes people more receptive to advertising messages are irredeemably flawed?

We asked Phil Barden, the author of Decoded: The Science Behind Why We Buy and managing director of decision science consultancy Decode Marketing, for his view on behavioural (or social) priming following Kahneman’s statements.

This is what he told us:

When someone as famous as Kahneman writes an open email calling, rightly, for action to counter the questions raised by the so-called ‘replication crisis’ centred on ‘social priming’ , there’s a tendency for those of us not working in academia to dismiss anything and everything to do with ‘priming’. However, I fear that would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Let’s start with a definition of priming in cognitive psychology from the American Psychological Association; priming is ‘the effect in which recent experience of a stimulus facilitates or inhibits later processing of the same or a similar stimulus’. This sounds a lot like ‘familiarity’, which is something we’ve known about for ages in marketing and advertising. Byron Sharp has written extensively about the benefits and power of familiarity i.e. prior experience of a brand makes a person more favourable to it.

We’ve also known for years about the effects of priming in market research; sometimes we do it deliberately by, for example, showing respondents an ad prior to gauging their reactions. Other times it can be an unwanted confound which affects research results.

Also, it’s not helpful to dismiss priming per se because there are many different types of priming. The priming to which Kahneman referred is known as ‘social priming’ yet, even in this field, there are studies which have shown replicable results.

For example, the idea that ‘watching eyes’ can increase prosocial and reduce antisocial behaviour was supported by a meta-analysis by Dear et al (2019). Other types of priming include goal, affective, semantic and sensory and we use all of them in marketing: goal priming is how we target advertising messages e.g. those people who have a goal of being slim will have more positive attitudes to messages that contain words such as ‘gym’ or ‘salad’.

Affective and semantic priming have been used for many years in quantitative implicit testing to test brand and touchpoint associations (if we’re primed with the word ‘fish’ then we’ll react faster to the word ‘chips’ than to the word ‘cricket’ for example).

Finally, sensory priming is used extensively by food and beverage manufacturers, the hospitality industry and retailers, and Professor Charles Spence at Oxford University has done incredible work in this space.

The colours, sounds and scents that we perceive (freshly baked bread on entering a supermarket for example) and even the glassware, crockery and cutlery that we use in a restaurant may well have been carefully crafted to enhance our experience.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.