How the right kind of sorry can help brands move on /

Marketing is a foggy business but at least one thing is becoming clearer with each passing day – at some point you’ll be sorry.

James Swift

/

Perhaps it’s because brands today pump out so much content across so many channels that gaffes are more common. Or perhaps seeking more meaningful relationships with consumers has lumbered brands with new obligations. But brand apologies are being made thick and fast, and there’s no reason to think they’ll stop.

No one thing is tripping up brands and prompting all these apologies. Bakery chain Greggs was brought low over its advent calendar that substituted Jesus Christ for a sausage roll, while Facebook is having to make up for destabilising Western democracy. The point is you won’t always see the trouble coming but you can control how you respond. And a good apology can be the difference between a fresh start and a permanent blot.

When /

First let’s address when you should deliver the apology. You might think the sooner the better, that an apology delivered too late looks like capitulation rather than contrition. To some extent, acting quickly is a good rule of thumb. Corporates often hesitate when considering whether to eat crow but they shouldn’t, say professors Maurice Schweitzer and Alison Wood Brooks in Harvard Business Review: ‘Most apologies are low cost and many create substantial value. They can help defuse a tense situation and fears of litigation are often unfounded.’ Hospitals have even saved money on law suits by encouraging surgeons to apologise quickly and candidly for their mistakes. One study estimated that apologies, on average, reduced payouts by $32,000.

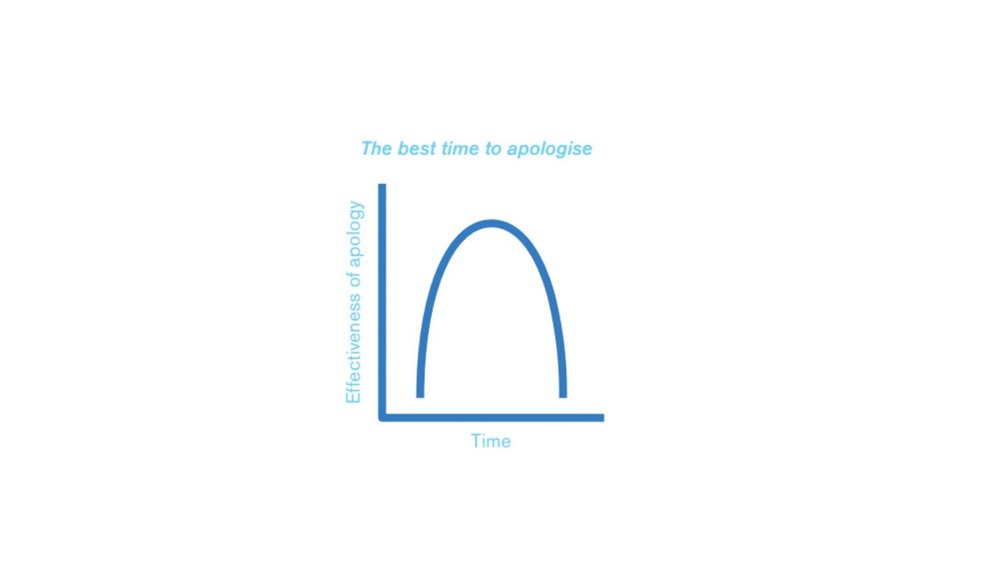

But there is some nuance to timing an apology perfectly. Frank Partnoy, author of Wait: The Art and Science of Delay, argues the severity of a transgression dictates when your apology should arrive. If you’re saying sorry for something awful, give the aggrieved parties a chance to process and voice their anger before prostrating yourself. A graph depicting the best time to apologise would be n-shaped, not a straight line. But the scale of the x-axis would be vague at best.

Where /

Fortunately the question of where you should apologise is more straightforward. If you’re saying sorry for an offensive ad or for some other minor screw-up, then a social media post is enough. Apple ended its feud with Taylor Swift by tweeting that it was reversing its policy of not paying artist royalties during customer trial periods and, a short while later, Swift was appearing in ads for the brand.

Buggering up your core offering means that, if possible, you should contact everyone affected and offer to make amends. It also means going into print. A full-page ad of grovelling text in a paper of record shows you’re taking things seriously.

If you’ve done something truly heinous – systematically cheated customers, killed people, etc – then you’re going to have to go on TV. US viewers tuning into the NBA playoffs last summer were bombarded with big-budget mea culpas from Uber (below), Wells Fargo (now removed from the internet) and Facebook, all of which were battling to save their corporate reputations.

A word of warning, though: if you’re going to stick your CEO in the ad (and it’s not a bad idea) make sure they know how to look sorry. A study, published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, analysed 29 video apologies from executives and then tracked their company’s stock price. The more a leader smiled, the further shares plunged. But executives that gave particularly doleful performances saw their company stock rise a little. So don’t be afraid to lay it on thick.

How /

Once you take your ego out of the equation, saying sorry is not complicated. Aaron Lazare, who wrote On Apology, divides successful apologies into four parts: acknowledgement, explanation, remorse and repair. Others say there are three components to a good apology: candour, remorse and change. Whichever template you use, most brands fall at the first hurdle. Neither Wells Fargo nor Facebook acknowledged wrong-doing in their ads in any meaningful way. They just reminded people why they loved the company in the first place, briefly alluded to things going wrong and then spent the rest of the slot saying how they were making things better. Uber didn’t even come close to spitting out anything that resembled ‘sorry’.

The only sin more cardinal than not saying sorry at all is saying ‘sorry if…’. Apologising for the wronged party’s reaction, rather than the transgression itself, shifts the blame. Before social media, this kind of linguistic jujitsu used to pass muster, but people are wise to it now. Saying ‘we missed the mark’ (like Pepsi did in the wake of its awful Kendall Jenner ad) isn’t quite as bad, but it’s so common that it looks as if you pulled the statement from the Ladybird Book of Crisis Comms and should be avoided.

The creative choice /

Given how often brands botch the simple stuff, it would be wrong to advise injecting creativity into your brand’s apology – with one exception. If you have a logistical or supply issue that prevents your product getting to consumers, go nuts. KFC’s now-famous FCK ad, apologising for a chicken shortage, was judged to be pitch perfect. Before that, Johnson & Johnson won back the hearts of customers upset that its OB tampons were unavailable by sending them a video of a humorous, amateurishly personalised, love song.

There is no logic to this exception. Maybe the balance of power shifts when brands realise just how much people want their products, fortifying them to take creative risks. Or maybe there are now so many brand apologies to analyse that I’m starting to imagine non-existent patterns, like an inveterate gambler staring at a form guide.

A brand’s only other option is to tell the world to go to hell. When the Portman Group claimed that BrewDog had broken alcohol marketing rules with its Dead Pony Club ale packaging, the brewers responded by saying ‘sorry for never giving a shit about anything the Portman Group has to say’. But BrewDog only did this because it had already established itself as a punky brand and because it guessed its customers couldn’t care less about the Portman Group.

For most brands, the best advice is just to apologise promptly and do it right so that you only have to do it once. Nothing undermines contrition like being forced to re-apologise, and ‘sorry’ loses its potency the more you say it.

If in doubt, just remember the words of 19th-century theologian Tryon Edwards: ‘Right actions in the future are the best apologies for bad actions in the past.’

Contagious is a resource that helps brands and agencies achieve the best in commercial creativity. Find out more about Contagious membership here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.