The right reply: how brands can navigate public requests /

At any moment your brand could be surprised by an unexpected request that goes viral and catapults it into the spotlight. How should marketers maximise these opportunities – or at least escape the hype unscathed.

Sunil Bajaj

/

In May 2011, UK supermarket chain Sainsbury’s received a letter from a young girl called Lily Robinson. She was curious as to why one of the company’s loaves was called tiger bread, suggesting that giraffe bread was a more fitting name for the patterned bloomer.

Customer manager Chris King replied to Lily with a letter commending her brilliant idea, along with a £3 ($4) gift card so she could purchase a loaf of ‘giraffe bread’ next time she visited a Sainsbury’s.

Lily’s mother posted the exchange on a blog, which eventually went viral – with a dedicated Facebook page accumulating 150,000 Likes. In January 2012 Sainsbury’s took the suggestion a step further, officially renaming the loaf ‘giraffe bread’ nationwide – a permanent change that can still be found in its stores nearly a decade later.

The online requests that brands now receive are often noisier and less wholesome, with responses being a lot riskier. When a crowd starts forming and the pressure begins to mount, it’s tempting to say or do anything to get them to go away happy – but brands need to put a good amount of thought into a response if they don’t want to risk the mob pulling out their pitchforks.

To help you land on the best course of action, we’ve examined some of the most high-profile requests from the past few years and put together some guidelines on how to react when you find yourself on the sharp end of a viral demand.

Feeding the hungry /

The first hurdle for brands responding to a product request that’s gone viral is to discern how much of the noise is people piggybacking on a ‘hilarious’ meme versus actually wanting to get the product for themselves.

McDonald’s was faced with this issue on 1 April 2017 when animated TV show Rick & Morty aired a surprise season three premiere on channel Adult Swim.

The episode made several references to Szechuan Sauce, a discontinued McDonald’s McNuggets condiment that was first used to promote the Disney movie Mulan in 1998.

The official Rick & Morty Twitter account then tweeted the following day: ‘Please god, I don’t ask for much, please let us gain enough cultural influence to force McDonald’s into bringing back that fucking sauce.’ This instantly whipped up fans into a frenzy and got them demanding that McDonald’s bring it back.

The fast food giant initially capitalised on the opportunity with impressive fluency, resurfacing the recipe, ensuring it tasted true to the original and launching a social contest to give a few lucky people the chance to win a half-gallon bottle for themselves. But as demand for the sauce continued, McDonald’s decided to make some riskier moves, aiming to bring Szechuan Sauce back to tie in with the launch of its new buttermilk crispy tenders on 7 October.

McDonald’s produced 4,000 pots of Szechuan Sauce for the one-day-only event, sending them out to 200 participating restaurants. (For context, there were more than 14,000 McDonald’s locations across the US in 2017.) What transpired was hundreds of fans travelling across state lines only to discover upon arrival that many of the restaurants never received their shipment of sauce. For the locations that did, there were only 20 pots available to satiate all those people hungry for meme sauce.

In a three-part branded podcast called The Sauce, which investigated what happened, McDonald’s director of social media Paul Madson said that ‘the pictures we saw of people pitching tents and sitting on lawn chairs outside of our restaurants very quickly turned into angry chants and pictures of police and emergency vehicles parked outside of our restaurants. Basically the combination of things that you never want to see in real life, let alone on the internet, for everyone to look at.’

Typically for a release of this scale, McDonald’s would require testing in smaller markets to assess demand. But to ensure Szechuan Sauce tied into this product launch and capitalised on the cultural moment, the brand bypassed its own safety checks and entered unchartered territory. This led to what the media called ‘the Szechuan Sauce riots’, resulting in negative headlines around the world and an overwhelming number of disgruntled customers tweeting at the brand.

All of this could have been avoided if McDonald’s had done its maths correctly. It was clear from the hubbub that people wanted Szechuan Sauce to return, but the QSR failed to investigate just how many people would actually turn up and whether its supply of sauce would satisfy all those consumers.

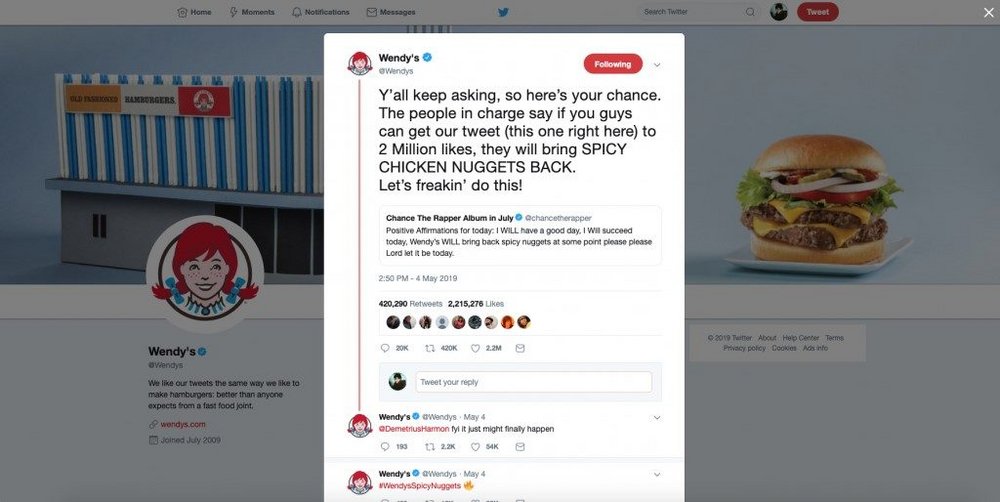

In contrast, when Chance the Rapper asked fast food chain Wendy’s to bring back its spicy chicken nuggets in 2019, the brand set a benchmark of 2 million Likes before it would honour the request – a target that took just 48 hours to reach. If like Wendy’s, McDonald’s had better gauged the purchase intent, the brand would have had a clearer picture of the situation and could have adjusted the launch date accordingly.

You might want to reconsider giving in to a viral request if it creates unrealistic demands that simply cannot be met. Or at the very least, if your supply chain can’t keep up, manage expectations to prevent any backlash.

When it comes to a limited-edition fashion drops from the likes of streetwear brand Supreme, people get that potential disappointment is part of the experience, but they expect dependability from the world’s biggest fast food chain – herein lies the compounding factor as to why McDonald’s attempt to join in on the joke fell flat.

Sunil Bajaj, Contagious

Cruel intentions /

Even if a request might be relatively manageable to meet that doesn’t always mean it is in a brand’s best interest to actually respond. Companies need to consider the intentions behind the request and weigh up the risks involved against the possible earned media of capitalising on an unexpected opportunity.

On 7 December 2020, comedian and late-night talk show host John Oliver created a YouTube video during the winter hiatus from his news satire show Last Week Tonight. The video addresses a throwaway joke from the show’s previous season that questions what the mascot of Pringles looks like from the neck down – something the brand had never shown.

He explains that after the show aired, many people tweeted fan drawings of Julius Pringles’ body, depicting the moustachioed man as everything from an octopus to a BDSM enthusiast. Oliver signed off with an offer to donate $10,000 dollars to food bank charity Feeding America if Pringles could simply answer the question of what the mascot’s body looks like.

While the video was rocketing towards 4 million views in just 48 hours, Pringles jumped at the chance to respond – it messaged Oliver the day his video dropped, saying it would reveal all the next day. True to its word, the brand dropped a 14-second video with a very ordinary looking Julius Pringle, dressed in a red suit and white T-shirt, stood next to a Christmas tree. The brand also tweeted that it would match Oliver’s initial $10,000 donation.

Disappointed with the result, the official Last Week Tonight account tweeted, ‘Ok then! That’s by no means the answer we were hoping for, but that’s technically a response, so the donation to @FeedingAmerica is on its way.’

Fans chimed in with messages of support for the charity donations, as well as frustration at Pringles’ response. ‘I refreshed Twitter all day for that? Meh. I like the fan pics more,’ tweeted one. ‘This reveal was the most disappointing thing on the internet this year and I’m saying this fully aware that we are in 2020,’ wrote another.

Unlike the giraffe bread request, which originated from a three-year-old girl, Pringles was dealing with a 44-year-old satirist who in no way masked his disdain for the brand. His video is peppered with negative comments, such as ‘Pringles: the product that looked at potato chips and inexplicably thought, “What about that, but worse, and delivered via tube.”’ Oliver also described Pringles as a ‘garbage snack’, offering the caveat that Feeding America will only get his donation if the charity agrees not to ‘spend a fucking penny of that money on Pringles’.

A brand needs to look at the motives behind any appeal for action – context is all important, and missing the nuances of a request could result in more harm than good. There is a lot of pressure on brands to act quickly to whatever is happening online – Pringles certainly seized the cultural moment, responding to Oliver’s request in just 24 hours. But had it taken longer to assess the situation then the outcome here may have been different. Should the brand have humoured a comedian publicly trash-talking its brand and product – despite the charity donation offer holding it hostage? Or should it have just worked harder on its creative execution? Whatever the brand did, it should probably have taken a beat to produce a more considered response that was more appropriate to the snarky tone of Oliver’s original video.

Listen up /

What happened to McDonald’s and Pringles shows what happens – for better or worse – when brands are hounded by a vocal minority, but sometimes brands need to pay attention to some of the less aggressive requests of their social media fans.

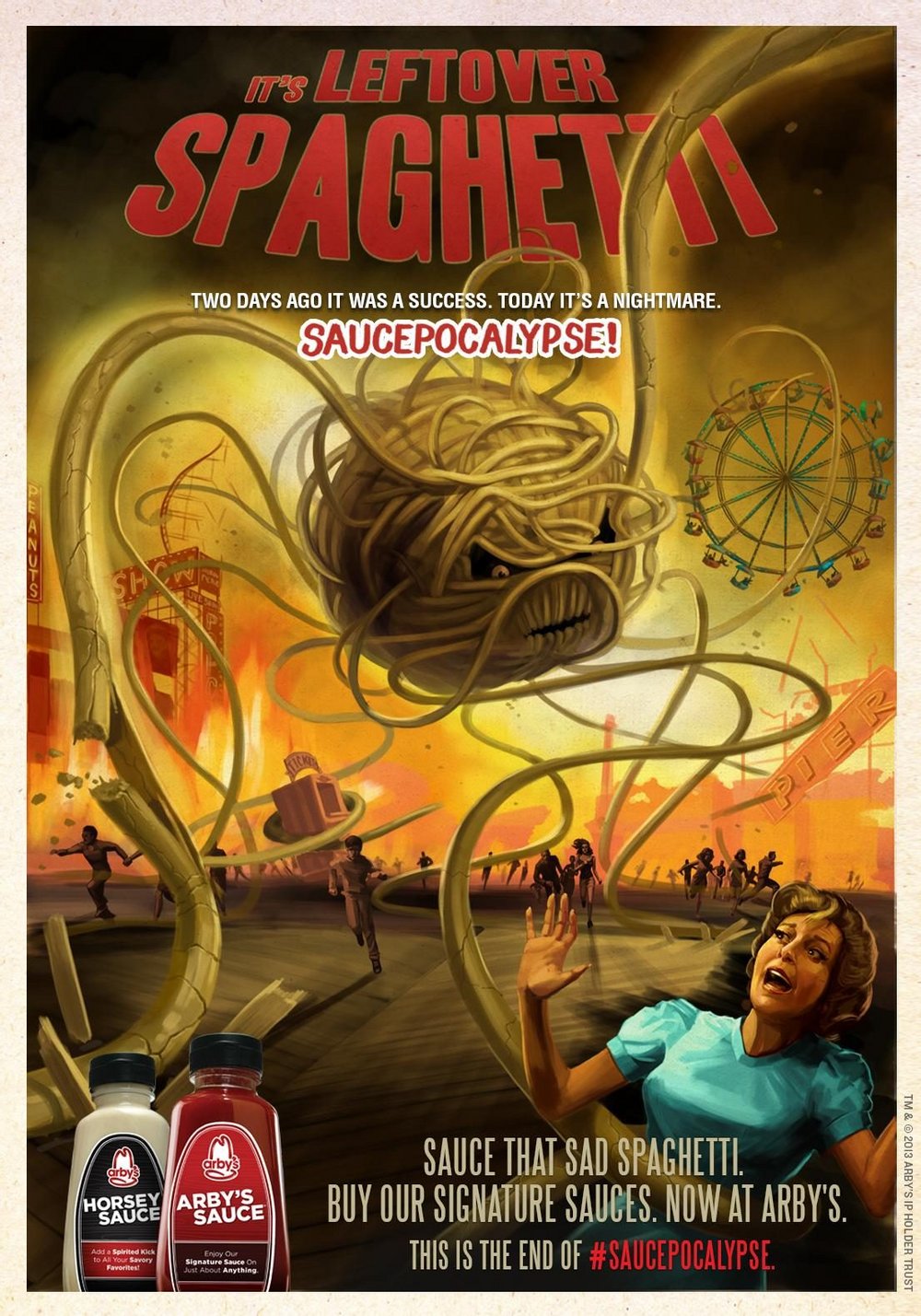

US sandwich chain Arby’s discovered that a third of all online comments directed towards the brand related to wanting, needing or running out of its signature sauce. This insight resulted in Arby’s bottling its sauce and bringing it to market in the US, launching with a campaign that anchored on the idea of people being scared of running out of the condiment.

Arby’s called this nightmare scenario the Saucepocalypse, inviting people to post their horror stories of being sauceless during important moments. Working with agency Crispin Porter Bogusky, Boulder, Colorado, these real-life tales were then turned into old-school Hollywood movie posters such as Mom’s Mad Meatloaf, Invasion of the Sauceless BBQ and Beer Can Chickenstein.

As well as being released in print, these ads were made into billboards that appeared in the towns of the people who submitted their horror stories. According to Arby’s, the brand sold more than 50,000 bottles of sauce and generated over 500,000 media impressions – making the Saucepocalypse one of the best product-extension launches in the brand’s history.

You won’t always have the starting point of a viral request and you may have to dig for the right opportunity to respond to customers, like Arby’s, but it could be worth it as publicly acknowledging requests humanises brands and shows customers that they are being listened to. It can provide real value too, as, according to a study by Applied Science Marketing, consumers who receive responses to their tweets are willing to spend 3% to 20% more on average-priced items.

If you build it, they will come /

While McDonald’s and Pringles were faced with one-off requests, some brands are frequently targeted by fans or customers making specific demands. One brand that often finds itself on the receiving end is Lego.

In the 2000s, the Danish toy brand began collaborating with some of the world’s biggest entertainment properties, such as Star Wars, Harry Potter, The Simpsons, Super Mario and Minecraft, and this has encouraged fans to request their own dream builds.

To help streamline this process, the brand launched Lego Cuusoo in 2008 – a platform where fans in Japan could submit their own Lego designs to be made into sets. If they reached 1,000 Likes, Lego commissioned the set to be sold at toy stores across the country.

In 2014, the crowdsourcing platform was rebranded to Lego Ideas and went global, becoming a community with 1.8 million members. This has helped the brand filter down from 35,000 suggested concepts to just 34 builds – these select few achieving the required 10,000 votes and then signed-off for creation following an internal review by Lego.

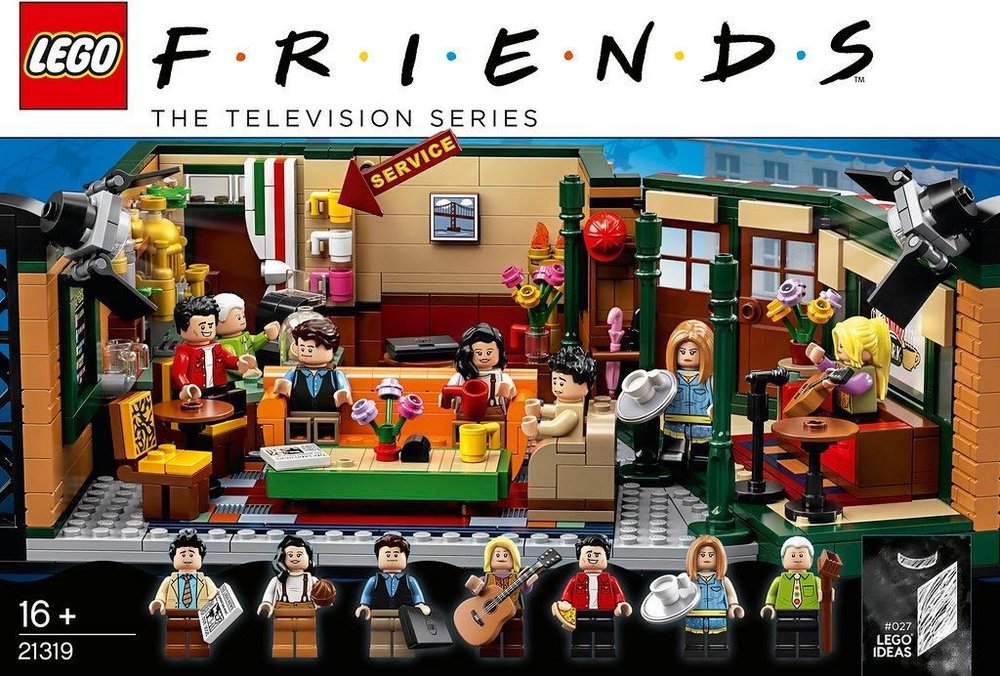

Since then, inspired by fans, Lego has launched sets for Back To The Future’s DeLorean and the Central Perk coffee shop from Friends. It has also responded to more high-brow requests with builds including the Women from Nasa set and a replica of Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

Your brand might not need to implement a system as sophisticated as Lego Ideas, but if you are repeatedly inundated with requests for new products online, then establishing a process to sift through them all would be extremely prudent.

Reply all? /

As we’ve seen, responding to viral requests is deceptively challenging because there is a balance to be struck between matching the speed of the internet and putting time and thought into a response.

As a brand, it’s not enough to simply acknowledge a customer’s tweet and provide an answer. Do your homework and think about what it is that people expect of you. Who are you dealing with – a real fan or someone trying to make you the butt of a joke? Are there any requests you need to work harder to listen to? Could you put a system in place to show your customers that you’re listening to their ideas? Whatever you do, don’t fall prey to the easy slip-ups that can be avoided with enough preparation, co-ordination and imagination – that’s our simple request to you.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.