Is the creative awards crisis a symptom of a bigger effectiveness problem in advertising? /

Is the dwindling potency of creatively awarded campaigns a symptom of a more general crisis in advertising effectiveness?

James Swift

/

Marketing consultant Peter Field took a trip to the basement of the Palais convention centre at Cannes this year and he did not like what he saw.

He had gone down there to look at the shortlisted work and was disappointed to discover ‘an ocean of disposable, short-term ideas’.

‘Many of them were very nice,’ he says, ‘but you think, “Why didn’t they make a proper campaign out of it?”’

Field’s visit to the Palais only confirmed what he had come to the Riviera to tell agencies and brands anyway: that the work being celebrated as the pinnacle of creative advertising was now no more effective than non-awarded work.

It was an alarming message that, according to Field, ‘struck a chord with a lot of people who were concerned with the way that [advertising] awards had been going’.

But the problems uncovered by Field's research do not end with industry awards shows. Field believes that the declining potency of creatively awarded work is just a symptom of a more general crisis in advertising effectiveness. Is he right?

Bursting the awards bubble /

Over the past decade, Field has established himself as a preeminent voice in advertising effectiveness. Since 2013 Field and his regular research partner, Adam&eveDDB’s Les Binet, have been warning that advertising effectiveness was being dragged down by brands over-investing in short-term activations at the expense of long-term brand building.

But their warnings have gone unheeded and in his latest report, The Crisis In Creative Effectiveness, Field straps on his sandwich board and picks up his bell to herald the arrival of the advertising effectiveness apocalypse.

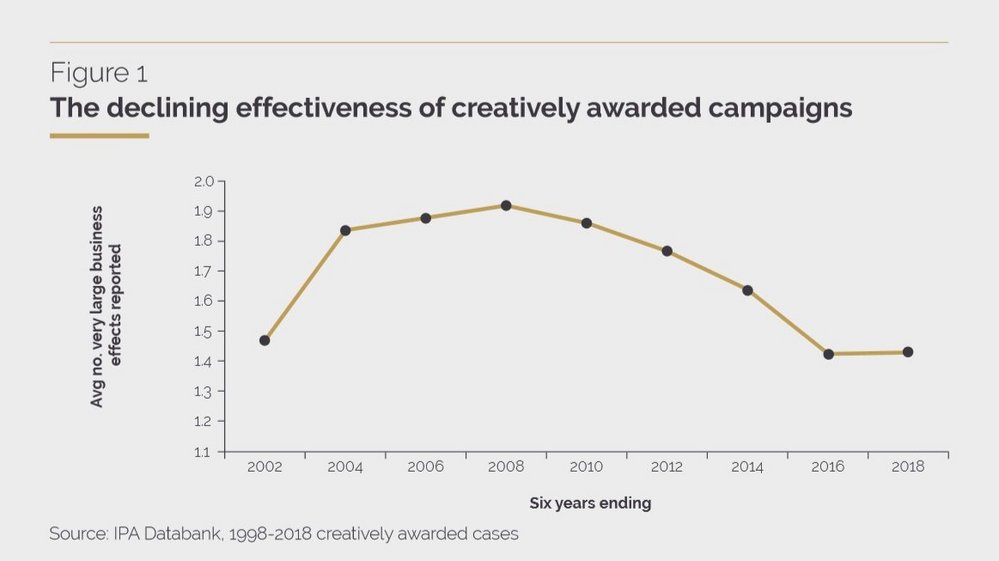

The report cross references case studies submitted to the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) with creative awards data to examine the effectiveness of celebrated campaigns. In the 12-year period between 1996 and 2008, creatively awarded work was typically 12 times more efficient at driving returns than non-awarded work. But that multiplier drops to four if you measure the same data between 2006 and 2018. And if you isolated just the past few years of awarded work, the advantage in creatively awarded work would be wiped out entirely, says Field.

Field links the decline to a proliferation in short-term sales activations among the awarded work. These are campaigns that track results over a period of less than six months and that, typically, nudge people to act immediately by offering a discount or by promoting some new product feature. These campaigns are winning awards, says Field, at the expense of emotional brand-building campaigns that establish durable memory structures in people’s minds over a long period of time.

‘If you put enough money behind [short-term ads]’ says Field, ‘eventually you will get a brand that is differentiated on some performance level […] it’s just a case of, “How much time and money have you got?”’

The Crisis In Creative Effectiveness report doesn’t explain why awards juries seem to now prefer short-term activations to long-term brand-building campaigns. But Field has his suspicions. He points to a statistic that award-winning short-term campaigns on average spend 2.5 times more on online media than long-term campaigns – suggesting that awards juries, like everyone else in the industry, lose their faculties in the presence of shiny new tech and media.

The report also cannot prove that the effectiveness crisis exists outside advertising awards shows, because it only examines awarded campaigns, but Field is adamant that it does: ‘I think it would be very surprising if the kinds of findings we’d been picking up in the IPA database weren’t also true of the broader world of advertising.'

Happy ending /

Orlando Wood, the chief innovation officer at global marketing research and effectiveness company System1 (formerly BrainJuicer), tells Contagious that Field is correct. He says that the declining effectiveness of awards show winners ‘is a part of a broader trend’ and that it is proved by System1's proprietary test, which measures people’s emotional response to an ad to predict its potential to drive brand growth.

Between July 2017 and June 2018, System1 measured every US and UK TV ad across six sectors (automotive, financial, FMCG, health and beauty, tech and charity) and found that over half only achieved a one-star rating (out of five), meaning they were expected to achieve zero market share gain for the brand in the long term.

The data is certainly persuasive, but System1’s test does not have the comparative data from years past to confirm that TV ad effectiveness has fallen. Wood can offer more circumstantial evidence, though. He notes that between 2007 and 2018 happiness scores of TV ads dropped from 51% to 28%, indicating that commercials no longer make people feel good as often as they did a decade ago.

Break time is over /

Wood knows more than a little about advertising effectiveness. He has written a book about the changing nature of advertising based upon an analysis of the ad breaks for long-running British soap Coronation Street. He tells Contagious that one of his more significant findings is that brands have steadily ditched fluency devices.

A fluency device is a term coined by Wood to describe characters, such as KFC’s Colonel Sanders, or scenarios, like those repeated by Snickers in its You’re Not You When You’re Hungry ads, that help people process a brand’s message.

‘In 1992 they accounted for about 41% of all ads on the IPA’s long-term database,’ says Wood, ‘and by 2016 they were only 12%.’ The result, says Wood, is ‘flatter and more devitalised work’.

Orlando Wood, System1

Asked whether he blames clients that demand short-term results, or agencies that let heads be turned from established principles of persuasion by new technologies, Wood says it is ‘both of those things and many more’.

Wood goes on to suggest that effectiveness has suffered because of more fundamental shifts that have taken place within agencies. ‘The industry has become a bit detached from the mainstream populace,’ he says. ‘The way now it thinks is more analytical than the mainstream. [Marketers are] in their own bubble and you can see it in the work, which has become very self-conscious and individualistic, and there’s less of a sense of community.’

Wood’s argument, that the people who make ads are cut off and aloof from the people who watch ads, also happens to chime with the results of a report published by Reach Solutions (the commercial arm of media owner Reach) in July.

The research compared a sample of 199 UK advertising and marketing professionals with 2,019 nationally representative adults. According to the qualitative study, not only are marketers no more empathetic or better at understanding people than the general population, they diverge from the mainstream in some key beliefs. Specifically, marketers are more likely to reject widely held beliefs that psychologist Jonathan Haidt referred to as the ethics of community (things like group loyalty and respect for hierarchies).

What both the research of Wood and Reach comes down to is that advertising has lost touch with what moves people and its effectiveness has suffered as a result.

Burden of proof /

Still, none of this amounts to an airtight corroboration of Field’s belief in an industry-wide effectiveness crisis.

In fact, as far as Contagious is aware there is no dataset in existence that proves beyond doubt that advertising effectiveness is declining across the board.

But that does not mean all is well with advertising effectiveness outside of awards shows.

The research cited in this article may not prove Field’s point with scientific certainty, but it indicates strongly that things are amiss.

The problem (or at least part of it) is that the issues raised by the research are large and unwieldy. Combating the flight to sales-focused digital campaigns and helping marketers reconnect with the mainstream means reversing an industry-wide inertia (one that has been caused by factors from without and within). When it comes to restoring the prestige of long-term populist brand building, there is, appropriately, no short-term fix

Contagious is a resource that helps brands and agencies achieve the best in commercial creativity. Find out more about Contagious membership here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.