The risky lure of brand sadfishing /

As children are warned of the dangers of sadfishing, it's a lesson that attention-hungry brands could stand to learn, too.

It’s time to finally open up about a major, life-changing struggle plaguing social media…sadfishing.

This is an online behaviour, worrying teachers and parents alike, where young people make exaggerated claims about their emotional problems in the hope of hooking a sympathetic audience.

Digital Awareness UK recently detailed the negative consequences of this new trend, putting the issue in the spotlight.

However, it’s no surprise that sadfishing has become prevalent when online influencers often use sadness and melodrama to win lucrative attention.

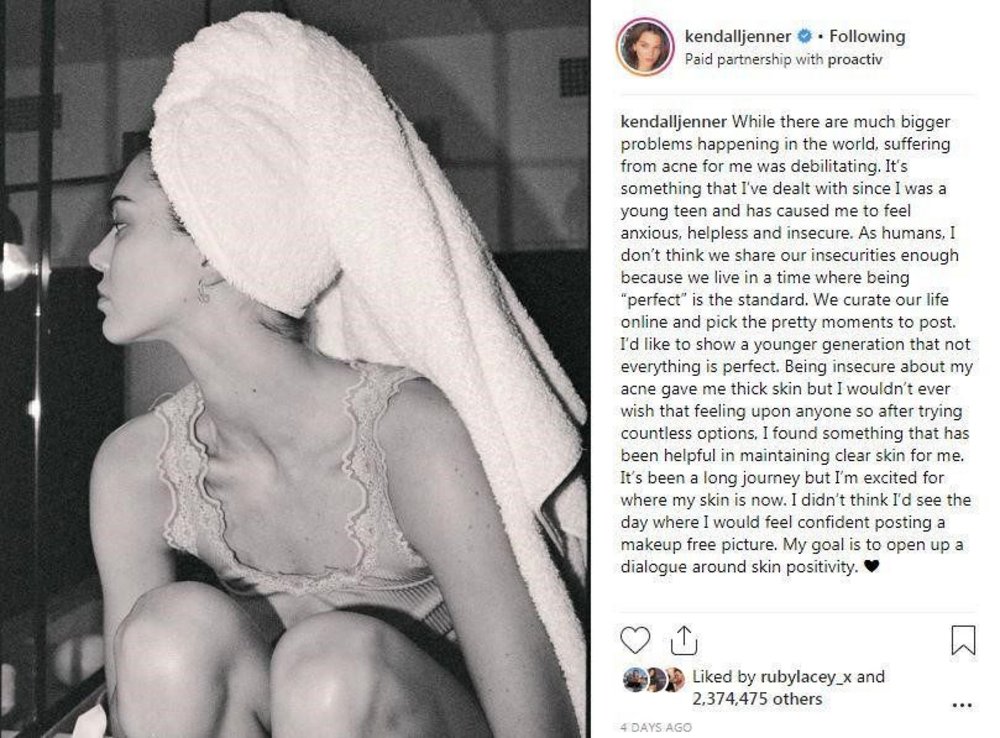

For example in January, Kendall Jenner (28.2 million Twitter followers) came under fire after her mother, Kris Jenner, sent a Tweet encouraging people to tune in to her daughter's feed in one week, when Kendall would reveal a ‘raw story’ about her life. The big announcement? She felt ‘anxious, helpless and insecure’ about having acne until she started using Proactiv skin cream, a brand that she was being paid to promote.

Jenner’s melodramatic product plug prompted a stampede of criticism. Similarly, Nashville influencer Tiffany Mitchell (216,000 Instagram followers) was ridiculed and abused after posting pictures to Instagram of her motorbike crash, which many said looked faked.

Mitchell denies she faked the crash, but that hasn’t stopped the public hypothesising that the influencer tried to gain attention (and promote a product) by staging a traumatic moment.

It’s not just online celebrities and influencers who are guilty (or accused) of tugging heartstrings to increase their reach, and it's not a new phenomenon, either. Brands do it too, and have done so for a while. In 2017, McDonald’s debuted an ad in which a mother told her son all of the ways that he wasn’t like his dead father, except for his preferred fast-food order.

More than 150 people complained about the ad to the Advertising Standards Authority, claiming it exploited child bereavement, and it was retracted.

Nationwide insurance pulled a similarly morbid and distasteful stunt during the Superbowl in 2015 by chronicling all the things a young boy was missing out on. Why? It was because he was dead.

The ad was heavily criticised on social media and 64% of the 240,000 comments made during the game were negative, according to Amobee Brand Intelligence.

The question is why do brands ratchet up sad emotions in sectors and circumstances where there is no real need, and does it actually work?

At a time when people are bombarded with as many as 5,000 ads per day, emotion helps brands stand out. A report released by Ipsos Mori details how emotional messages can be processed automatically, using lower levels of conscious attention and thus place a lower cognitive load on our processing and memory abilities.

Sad ads specifically increase brand value, according to a new study by AI-powered technology company Mirriad. The research revealed that there was a 17% increase in the perception of a brand’s value after watching an ad for a food and drinks company that was sad.

However, just because melodrama wins attention, that doesn’t mean that it will always result in the right reaction. Rather than furthering brand exposure, image and sales, emotionally exploitative advertising can damage them.

Civis Analytics, founded by the chief analytics officer on Barack Obama’s re-election campaign, analysed TV spots (as well as some digital and audio ads) from major companies. It revealed that while 75% of these ads were ineffective, 10% provoked a backlash. Although many brands think that being ignored is the worst possible outcome for ad, it's not. If a campaign annoys or offends people, it can damage sales, and, as we have seen from the examples above, people are quick to turn when they feel emotionally exploited.

Sad emotions in advertising have their place, but it’s a careful line brands must tread. When they cross that line they risk coming across as exploitative and inviting a backlash. Then they’ll really have something to be sad about.

Contagious is a resource that helps brands and agencies achieve the best in commercial creativity. Find out more about Contagious membership here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.