Hemispheres of Influence /

A new book pins the decline in advertising effectiveness on our collectively malfunctioning grey matter. James Swift asks if this is cerebral thinking or hare-brained guff

When the chief innovation officer at research agency System1 Group wanted to check the health of UK television advertising, he knew exactly where to stick the thermometer. It was somewhere cold, damp and frequently unpleasant – Coronation Street.

The British soap opera has been on the air and broadcast by the same channel for almost 60 years, and in that time has sustained its (relative) popularity with viewers and advertisers. It was the perfect specimen for Orlando Wood’s experiment. He identified week 40 as the least remarkable in Coronation Street’s annual schedule and then analysed 620 ads that aired in those commercial breaks between 1992 and 2019, to see what had changed over the years.

Wood discovered a decline in implicit communication (flirting, knowing glances), as well as unfolding dramatic scenes and cultural references. Regional accents became scarcer, as were scores with a discernible melody. Meanwhile, monologues and voiceovers that addressed the viewer directly grew more common; the same was true of words intruding on screen and adjectives posing as nouns. Wood also saw a trend towards ‘flatness’, by which he means a lack of depth or perspective.

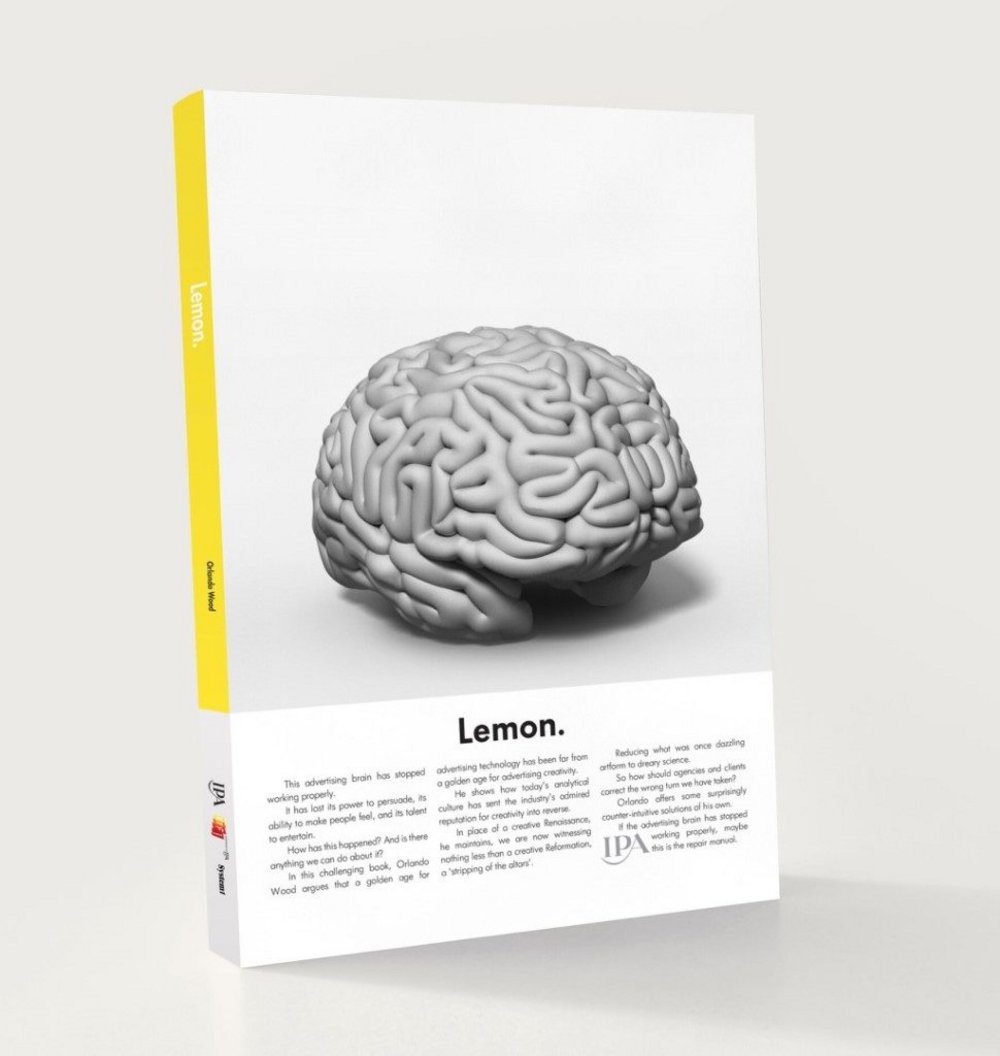

‘If this were art, then perhaps these changes wouldn’t matter so much,’ writes Wood in Lemon. How the Advertising Brain Turned Sour, his book detailing the experiment. ‘Except that advertising isn’t only an artform, it has a commercial purpose, and the effect of these changes is extremely damaging for advertising’s ability to deliver long-term market-share growth.’

Double trouble /

Wood is not the only one to find fault with modern advertising styles. Marketing consultant Peter Field came to similar conclusions in The Crisis in Creative Effectiveness (published in June by the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, which also published Lemon), and Wood borrows extensively from this report to help make his case.

Field used a trove of data to prove that creatively awarded work is now far less effective than it was and that this decline has been accompanied by an increase in short-term sales activations at the expense of long-term brand building campaigns. Like Wood, Field observed that this shift in style resulted in fewer emotionally engaging stories and more ‘didactic, literal presentations that seek to prompt us into action’.

But while Field refuses to speculate on what’s driving this shift to short-termism – save to briefly snipe at the awards juries in thrall to anything shiny and digital – Wood uses Lemon to point the finger at an unlikely culprit for advertising’s decline: the left hemisphere of the human brain.

The resurgent left /

For some people, the idea that the hemispheres of the brain do different things holds as much scientific weight as a Buzzfeed personality quiz. But in 2009 Dr Iain McGilchrist sought to rehabilitate the science of brain lateralisation with his book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, and Wood wholly buys into it. The thrust of McGilchrist’s argument is not that the different hemispheres have different jobs (it has been proven that both contribute to almost every brain function) but that each looks at things differently and has its own mode of attention.

The left hemisphere offers a narrow and focused sort of attention, and it understands things in a way that is abstracted and devoid of context. The right hemisphere attends to the world more broadly and holistically; it prefers living things and understands the way they relate to each other.

In optimal situations, the two hemispheres jostle for control evenly but sometimes one half of the brain (usually the left) dominates, causing all kinds of problems. McGilchrist theorises that this doesn’t just affect individual people but that entire societies can suffer a shared hemispheric imbalance that influences everything from science and commerce to art and culture. The art produced during the Renaissance for instance was lifelike, used perspective and often featured cultural references, indicating hemispheric balance (or right-brain dominance). Conversely the art of the Reformation eschewed depth and preferred symbolic representations of things; this was a period of left-brain dominance.

James Swift, Contagious

Entertain for gain /

Today, argues Wood, we are once again living under the yoke of the left brain. This is what’s driving the flatter, more literal and less human style of advertising, which is no good at creating the kinds of emotional associations that build brands, drive long-term sales and promote price elasticity.

To claw back that effectiveness, advertisers must return to advertising that embraces the ‘betweenness’ of human relationships, that is filled with cultural nods and references, and that uses metaphor and fluency devices (characters or scenarios that represent the brand message, eg the M&M’s mascots). Essentially, says Wood, advertising must once again learn to ‘entertain for commercial gain’.

No more magic /

Whether or not you accept the idea that the cultural output of entire civilisations is the result of a kind of shared psychosis, Wood’s argument that the ad industry can climb out of its miserable funk by imitating its more creative, more human past, is cogent and seductive. But if there is one criticism of Wood’s thesis, it’s that it downplays how much media and attention have changed in the time that Coronation Street has been on air.

Andre Redelinghuys, founder of South African agency Attention Lab, offers a thorough and lucid perspective in a Medium article, called ‘Marketing Pains’. He writes that the transparency and scrutiny of the internet means brands can no longer ply their magic by ‘filling information gaps with favourable perceptions’ and that brands now have ‘greater access to the ocean of attention, but [it’s] become a sea of shrinking fragments, where advertisers increasingly struggle to make personal connections’.

This is not to take away from the value of Lemon. Thanks to Wood, and to Field and others before him, we have a better idea of what ails advertising than at any other point in recent history. The diagnosis is complete, but the prognosis is still in the works.

Like knowing about marketing’s most important trends, insights and campaigns? Then come to Most Contagious in London on 5 December to discover everything that truly mattered in marketing in 2019 and what it means for 2020: Give us a day and we’ll give you a year.

Click this link for more information about the line-up and for tickets.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.