Why left-brain thinking is killing advertising effectiveness /

A new book finds the root of advertising's effectiveness problem within human physiology

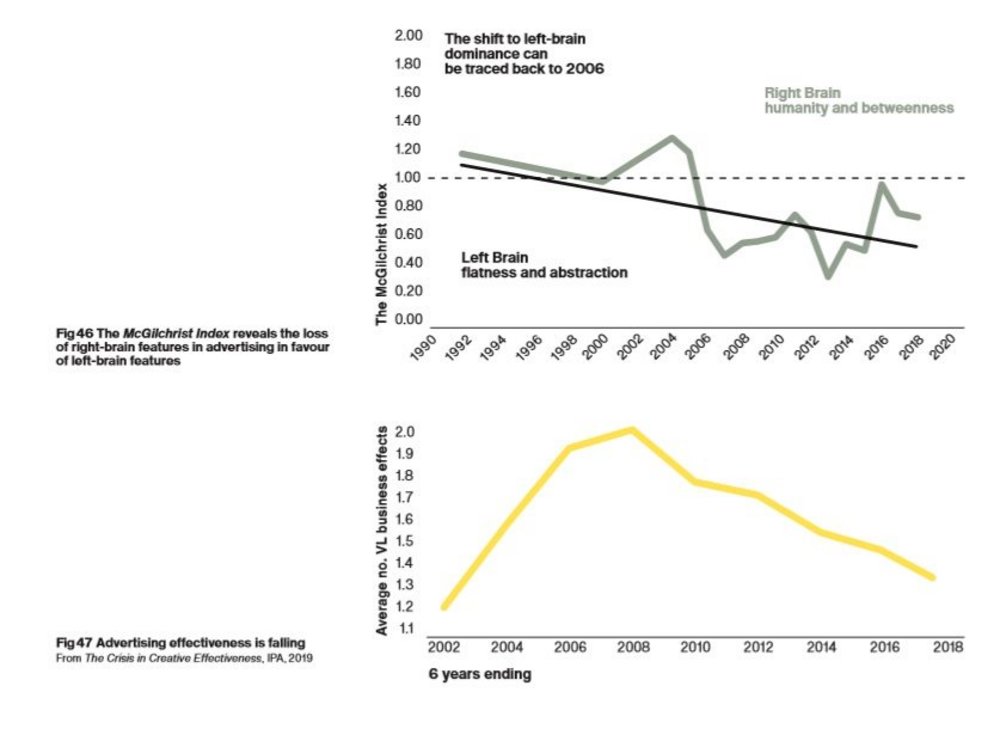

An epidemic of left-brained thinking is to blame for advertising’s plummeting effectiveness, according to a new book.

Lemon. How the advertising brain turned sour, was written by Orlando Wood, the chief innovation officer at advertising research agency System1 Group, and builds on Peter Field’s earlier exploration of what ails advertising.

‘This fall in campaign effectiveness has been hitherto explained by an increase in short-termism and the re-allocation of budgets towards activation,’ writes Wood. ‘But we now have another explanation for the fall in effectiveness: advertising style.

‘And the same attentional preference that lies behind short-termism, segmentation and tight targeting lies behind this shift in creative style.’

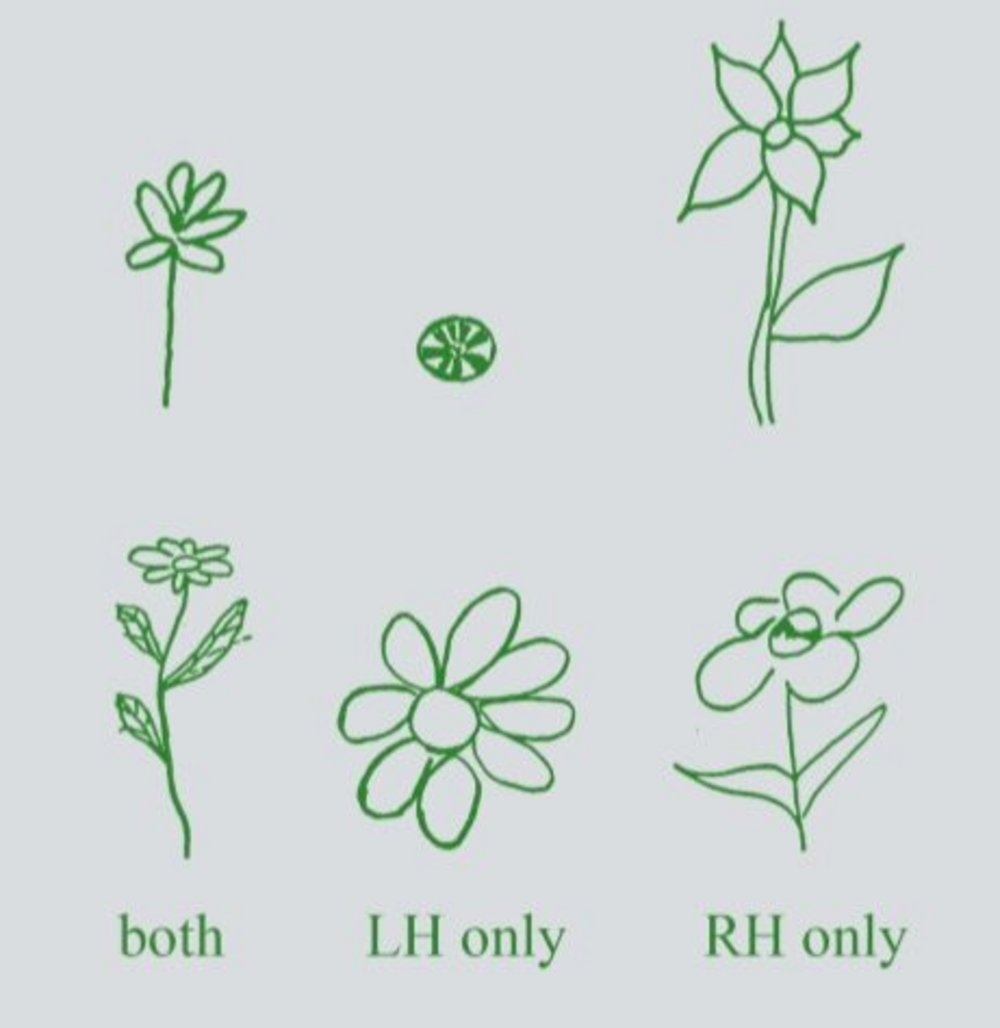

Image above: drawings of flowers from a study where participants used either their whole brain (both), left hemisphere only (LH) and right hemisphere (RH).

Wood’s thesis is based on the work of Dr Iain McGilchrist, who studied brain-damaged patients and concluded that the left and right hemispheres of the brain interpret the world differently.

‘It’s not that they do different things, as we used to think; it’s more that they do things differently,’ writes Wood.

Put simply, the left brain is narrowly-focused and prefers things to be abstracted and devoid of context. The right brain meanwhile has a broad attention; it has a preference for living things and understands how they relate to each other.

For reasons of physiology, the left brain is more able to suppress the right brain, and McGilchrist believes that hemispheric imbalance can spread throughout entire populations, influencing society and culture. Left-brain dominance is not exclusively bad, writes Wood, but it is ‘very limiting and causes many societal difficulties.’

To see McGilchrist’s theory in action, Wood says to compare the Renaissance with the Reformation. The art produced during the former was more lifelike. It also had more depth and included many cultural references. In contrast, the art produced during the Reformation was flattened and symbolic representations abounded: this was an era of left-brained dominance.

An example of Renaissance art (above) and Reformation art (below).

Like the Reformation, ‘the 21st century has ushered in a period of left-brain dominance’, argues Wood. People are making music, television shows and advertising that appeals to this hemisphere.

For example, chart music is more repetitive and homogenised, and more people are watching live sport and talent shows (which have rules and formats) than sitcoms (which celebrate relationships and ‘betweenness’).

Within advertising there are fewer displays of human connection, more monologues and voice-overs that address customers directly, and fewer cultural references, like pastiches or parodies.

Wood says campaigns that ‘turn descriptive adjectives into nouns’ – e.g. Nike’s ‘Find Your Fast’ – are also playing to the left brain’s preference for things over the living.

So too does advertising that sets out to shock or disrupt, such as the recent trend for anti-ads, like this from BrewDog, or the purposeful brand manifestos that pit values against each other, such as Nike’s Dream Crazy.

In the latter case it is because these ads tend to appeal to more individualistic values (e.g. care/harm), which are the domain of the left brain. The right brain is more concerned with what Wood describes as 'binding' values (e.g. loyalty/betrayal).

Still, some purposeful ads do appeal to the right-brain, according to Wood. He names Always’ Like A Girl as one such example, explaining that it trumpets its values in a way that does not seek to disrupt or divide.

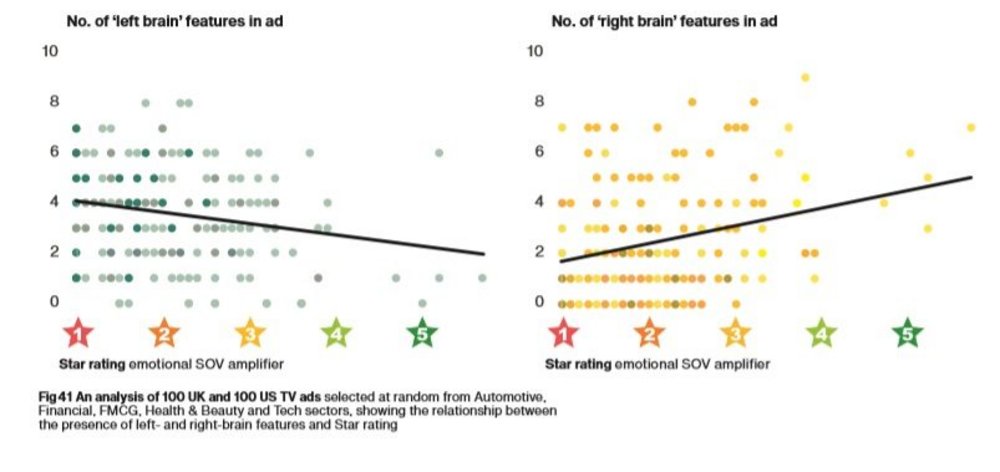

The effect of the dominance of left-brain thinking, says Wood, is ‘extremely damaging for advertising’s ability to deliver long-term market-share growth’, and he uses his own agency’s research to make his case. System1 Group selected 100 recent UK and US ads and found that ‘the greater the number of left-brain features in the ad, the less likely it is to achieve a strong star rating’. (The star rating is a proprietary system by which System1 Group claims to predict whether an ad will achieve major business results for a brand).

But the modern ad industry is not set up to resist the reign of the left hemisphere, according to Wood. On the contrary, the pressure put on agencies to create easily-repeated processes and to specialise, globalisation and many other facets of modern marketing are conducive to left-brain thinking.

If brands want more long term effectiveness from their advertising, they must fight the inertia and create campaigns that appeal to the right hemisphere of the brain: that means ads that are funny, celebrate human connections and use fluency devices (typically these are mascots but they can also be scenarios that represent the brand message e.g. ‘Should’ve gone to Specsavers').

Essentially, Wood argues, like so many other analysts, that advertising path back to effectiveness is to 'entertain for commercial gain'.

Contagious is a resource that helps brands and agencies achieve the best in commercial creativity. Find out more about Contagious membership here.

Want more of the same? /

We don’t just write about best-in-class campaigns, interviews and trends. Our Members also receive access to briefings, online training, webinars, live events and much more.